The US offers more organ-donor surgeries than ever, but more work is needed to improve organ transplants

David Tadevosian // Shutterstock

The US offers more organ-donor surgeries than ever, but more work is needed to improve organ transplants

Close-up of hands surgeons holding medical instruments.

Few things are as precious as a heart existing outside the body, in transit to another person who desperately awaits it. Meanwhile, the disparity between the number of heart donors and the number of heart transplants is growing—and this disparity extends to other facets of organ donation.

Medical teams performed more than 42,800 organ transplants in the U.S. in 2022, an increase of nearly 1,500 over the previous year. Yet, according to the nonprofit Bridgespan Group, 28,000 organs could be saved yearly if not for the current transplant system breakdowns.

Approximately 170 million people are registered organ donors, but each day an estimated 17 people in need of a transplant die waiting for a suitable organ. In cases where donors are deceased, which represents the majority of organ donations, the cause of death significantly impacts a donor’s eligibility. In fact, only 3 in 1,000 deceased candidates can donate, which makes a large supply of potential donors essential.

Citing data from the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network, Northwell Health partnered with Stacker to raise awareness concerning the organ donor shortage in the U.S. and explore what’s contributing to the gap between the number of available organs for transplant and the patients awaiting life-saving surgeries.

As a medical industry sector working to sustain patient lives, organ transplant has, of late, come under intense scrutiny. In August 2022, a Senate Finance Committee investigation cited a lack of oversight from the OPTN, leading to wasted organs, mistakes during screening processes, testing errors, blood type mix-ups, and other mistakes that led to 70 deaths and a further 249 patients contracting diseases.

To address these concerns and better serve patients in need of life-giving support, the Health Resources and Services Administration announced its “Modernization Initiative” in March 2023. The initiative emphasizes competition, transparency, and accountability to combat inefficiencies in the current transplant system. On the heels of the HRSA’s announcement, the Senate Finance Committee announced bipartisan legislation to break up the monopoly contract held by the United Network for Organ Sharing, giving the HRSA authority to overhaul the organ transplant system and open up OPTN contracting.

Read on to learn more about the gap between available organs and the patients waiting for them.

![]()

Northwell Health

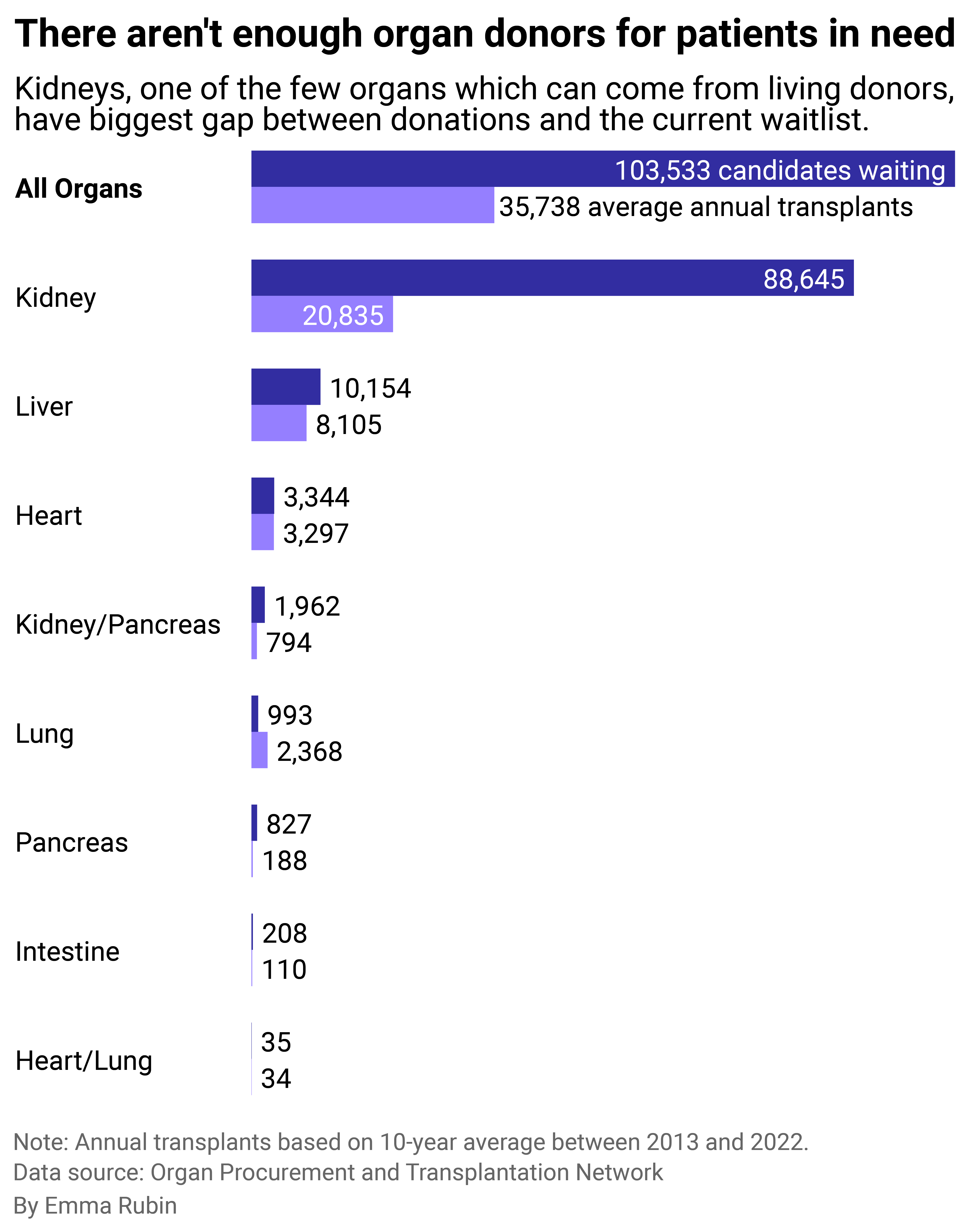

Kidneys have the biggest shortfall between the waiting list and organs available

Grouped bar chart showing there aren’t enough organ donors for patients in need.

Over the past decade, only 1 in 3 necessary organ transplants were performed on average.

The gap between the number of people who need a new organ and the average number of donations for that organ each year is the greatest for kidneys. Loss of kidney function or kidney failure is the most common reason for needing a kidney transplant, while diabetes and high blood pressure are what most commonly lead to kidney failure.

Unfortunately, just 23% of the people waiting for a kidney transplant are likely to receive one. A 2022 report from the OTPN stated 1 in 4 donated kidneys are discarded.

Most kidney discards occur after procurement biopsies, where organ procurement organizations examine a deceased donor’s organ for damage or disease and assess its viability for transplant. Some researchers question the validity of these biopsies, arguing the results are not reproducible while pointing to research showing kidneys discarded as low-quality in the U.S. are similar to kidneys transplanted with acceptable outcomes in France. Findings from another study published in 2019 explained transplant centers in France would have transplanted more than 60% of the nearly 28,000 donated kidneys discarded in the U.S. between 2004 and 2014.

In hopes of reducing discard rates and helping more patients in the U.S., researchers have called for better and more standardized evaluation methods to assess kidneys. Proposals include include incentivizing health care providers to consider the long-term benefits and cost-effectiveness of transplanting more types of kidneys. Others include diagnosing transplant viability at the molecular level and adopting a process used in Europe that identifies and expedites evaluation of kidneys at high risk of being discarded.

Northwell Health

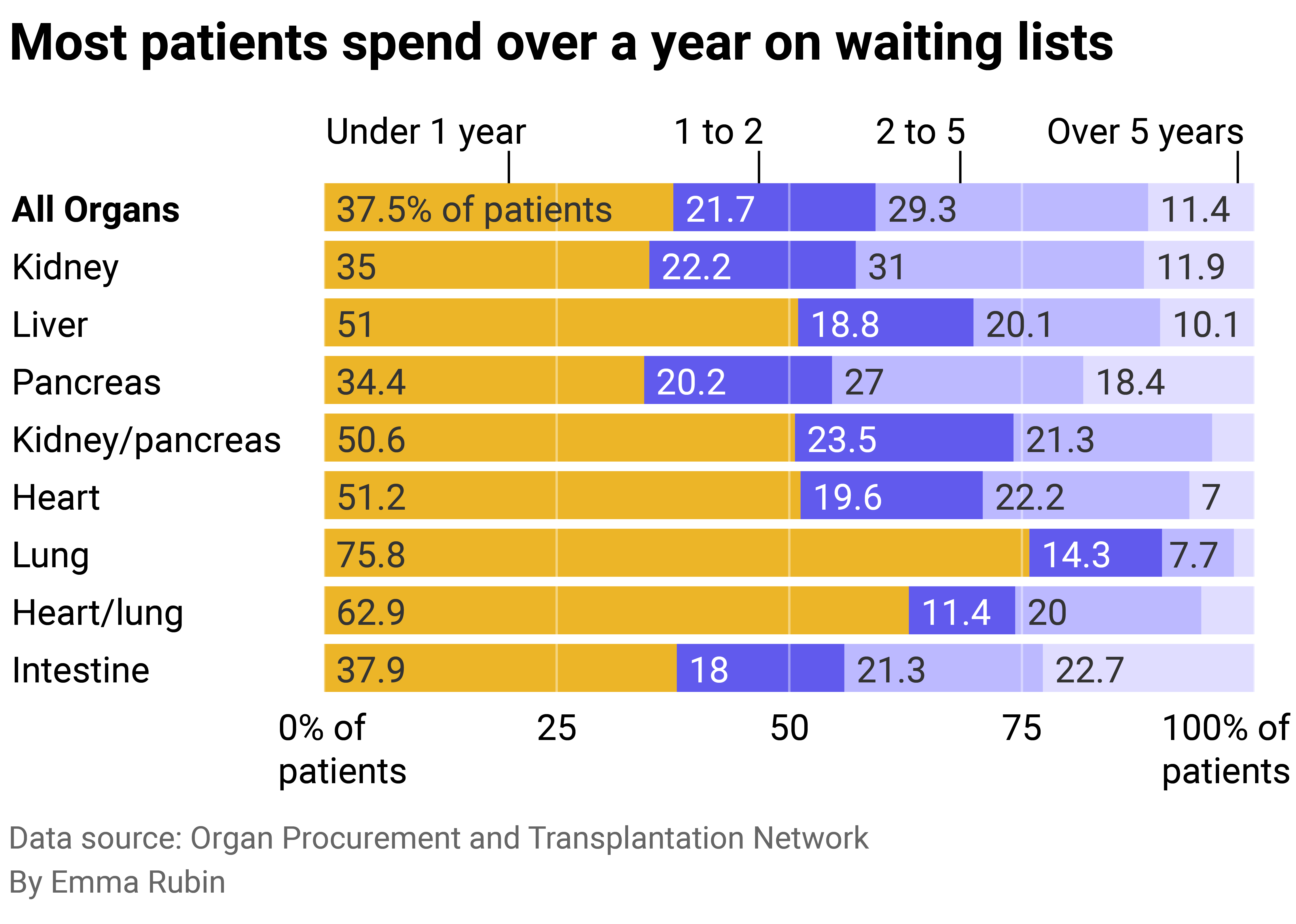

Wait times are long

Stacked bar chart showing most patients spend over a year on waiting lists.

Each day, 17 people die waiting for organ transplants. Most spend more than a year on waiting lists before receiving what is, in most cases, a life-saving surgery. Close to 250 hospitals across the U.S. perform transplants, and each hospital decides who it will accept. There are 56 organ procurement organizations responsible for organ recovery for transplant, as mandated by the government.

The OPTN considers some key factors for organ allocation to be fair consideration of candidates’ circumstances and medical needs, along with increasing the number of transplants and length of patients’ lives following a transplant.

Potential organ recipients can be on multiple waitlists, and doing so can decrease wait times. The United Network for Organ Sharing, which serves as the network manager for the Health Resources and Services Administration, currently operates a computer-matching program that considers medical factors such as blood type, medical urgency, and wait time when matching a donor to a potential recipient.

Northwell Health

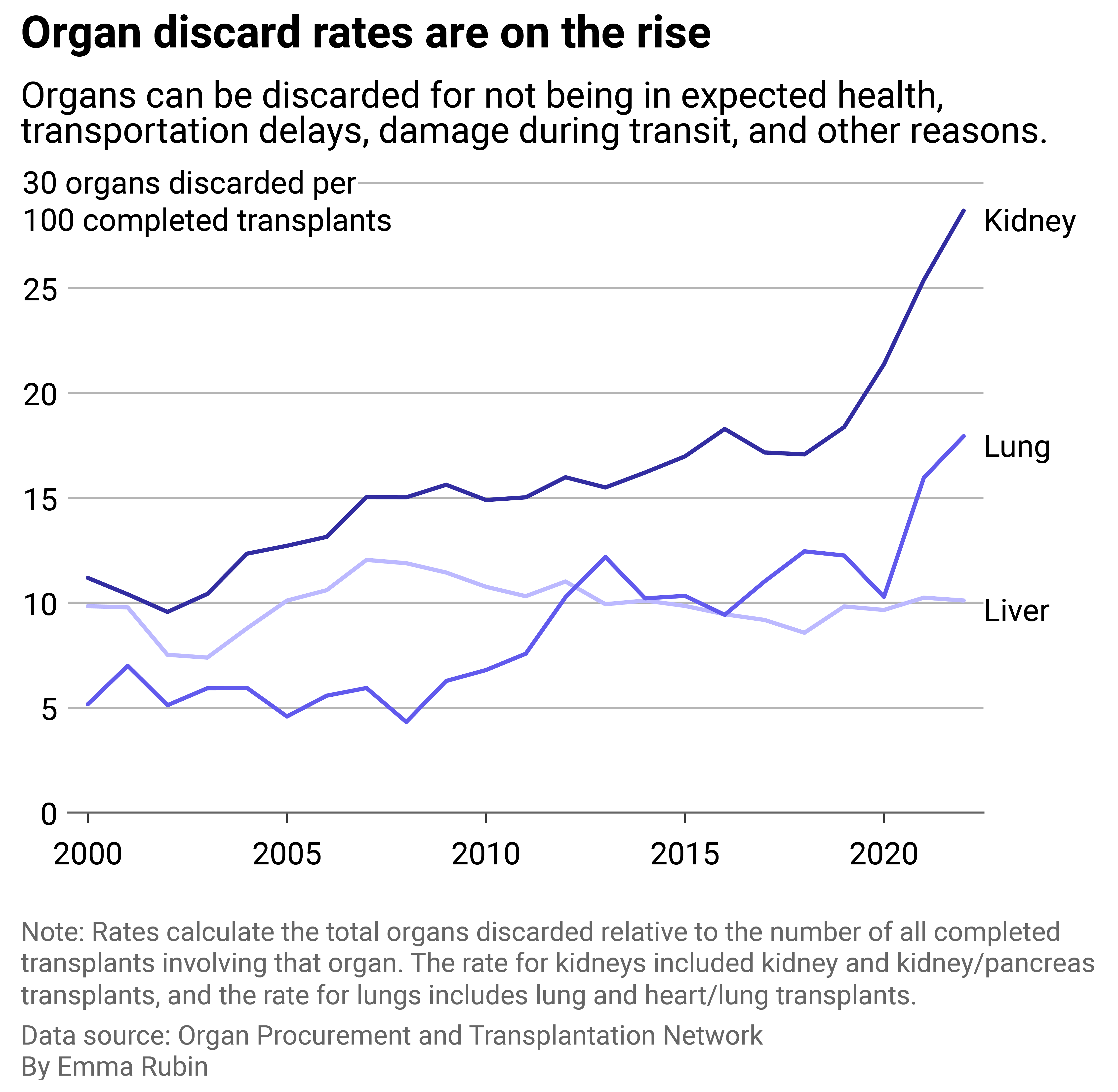

Despite needs, many organs still aren’t matched to a patient

Line chart showing organ discard rates are on the rise. Organs can be discarded for not being in expected health, transportation delays, and sometimes getting lost in transit.

Each internal organ has unique health considerations for transplant and maximum preservation time specific to that organ. A heart, for example, can be preserved for about four to six hours, while a liver can be viable for up to 12.

UNOS recently cast a spotlight on the liver’s more prolonged period of viability following a 2020 rule change that created what is known as “acuity circles,” by which patients in need within 500 nautical miles of a donor hospital will be given priority for a matching liver; if there is no patient in need at that hospital, however, the hospital will offer the liver to less ill patients at varying distances within that circle.

Nearly three years since this new rule went into effect, the Washington Post has reported both benefits and detriments to liver donation and transplant. While patients in several states, such as New York and California, have benefited from access to donor organs hundreds of miles from their nearest transplant hospital, patients living in lower-income states with higher death rates from liver disease have seen their chances of being matched to a donor organ decrease. Life-saving surgeries in states like Alabama, Louisiana, and Kansas have declined since 2019.

The Senate Finance Committee’s investigation of UNOS uncovered that couriers sometimes missed flights and left organs at airports, while some organs were never collected. According to the committee’s report, many of these mistakes resulted in the organ’s discard.

Out of the 56 government-chartered nonprofits that collect organs and make up an important part of the U.S. transplant system, some do not meet government requirements for collecting organs in their regions. And yet, despite that fact, they report on their own compliance.

Despite their viability outside the body of up to 36 hours, the rate of discarded donor kidneys became such an egregious issue that, in 2019, the Trump administration instituted new rules for reporting. It moved away from OPO self-compliance toward using independent data from the CDC.

Because the federal government recertifies OPOs every four years, the source of data reportage is critical to the integrity of organ transplant numbers. At the time, U.S. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Administrator Seema Verma pointed to metrics “riddled with exclusions” that effectively excluded “all but organs from perfect candidates.”

UNOS intends to meet the transplant community’s needs through several initiatives, including better data collection, transparency, and oversight. Along with organ procurement centers and travel companies involved in the organ transplant process, the network is currently working to develop algorithm-based route planning to streamline organ transplant transit routes with the potential to include real-time weather and traffic data.

Story editing by Brian Budzynski. Copy editing by Kristen Wegrzyn.

This story originally appeared on Northwell Health and was produced and

distributed in partnership with Stacker Studio.