These local governments are suing Big Oil

Canva

These local governments are suing Big Oil

A yellow offshore oil rig.

More than four decades ago, in 1978, Exxon science advisor James Black warned that “man has a time window of five to 10 years before the need for hard decisions regarding changes in energy strategies might become critical.”

Stanford University climate scientist John Laurmann in 1980 warned the American Petroleum Institute that if fossil fuels continued to be used, global warming would be “barely noticeable” by 2005 but would have “globally catastrophic effects” by the 2060s.

A 1982 internal memo from Exxon’s Environmental Affairs Program manager stated, “the consensus is that a doubling of atmospheric carbon dioxide from its pre-industrial revolution value would result in an average global temperature rise of 3.0 plus or minus 1.5° C. There is unanimous agreement in the scientific community that a temperature increase of this magnitude would bring about significant changes in the earth’s climate.” The memo noted that the time it would take to double atmospheric CO2 depended on global fossil fuel consumption.

CO2 levels today are up 50% since pre-industrial times.

In 1982, Exxon’s 40-page internal report on climate change nearly exactly predicted the amount of global warming, sea level rise, and drought we are experiencing today.

These documents, among others, are the foundation for dozens of lawsuits filed against Big Oil by states and municipalities in recent years. They allege the fossil fuel industry knew the detrimental impacts their products would have on the climate and not only continued to promote them but led deceptive campaigns to mislead the American people into believing that, at best, there was no risk and, at worst, the science was “uncertain.” Now, local governments are seeking to hold them financially accountable for the damage wrought by burning fossil fuels.

Stacker looked at the legal landscape of pending lawsuits against oil companies, citing data from the Center for Climate Integrity.

Since the first lawsuits against the fossil fuel industry were filed in 2017, oil companies have thrown huge resources into fighting these cases. Their primary—and best— argument was to move five cases from state court to federal court, arguing that damage lawsuits for climate change go beyond the limits of state law and are governed by federal law. Since there is no federal common law pertaining to greenhouse gases, these lawsuits would have surely failed in favor of oil companies.

In April 2023, the Supreme Court declined to hear challenges, allowing these cases to play out in state courts, in a huge victory for local governments.

![]()

Stacker

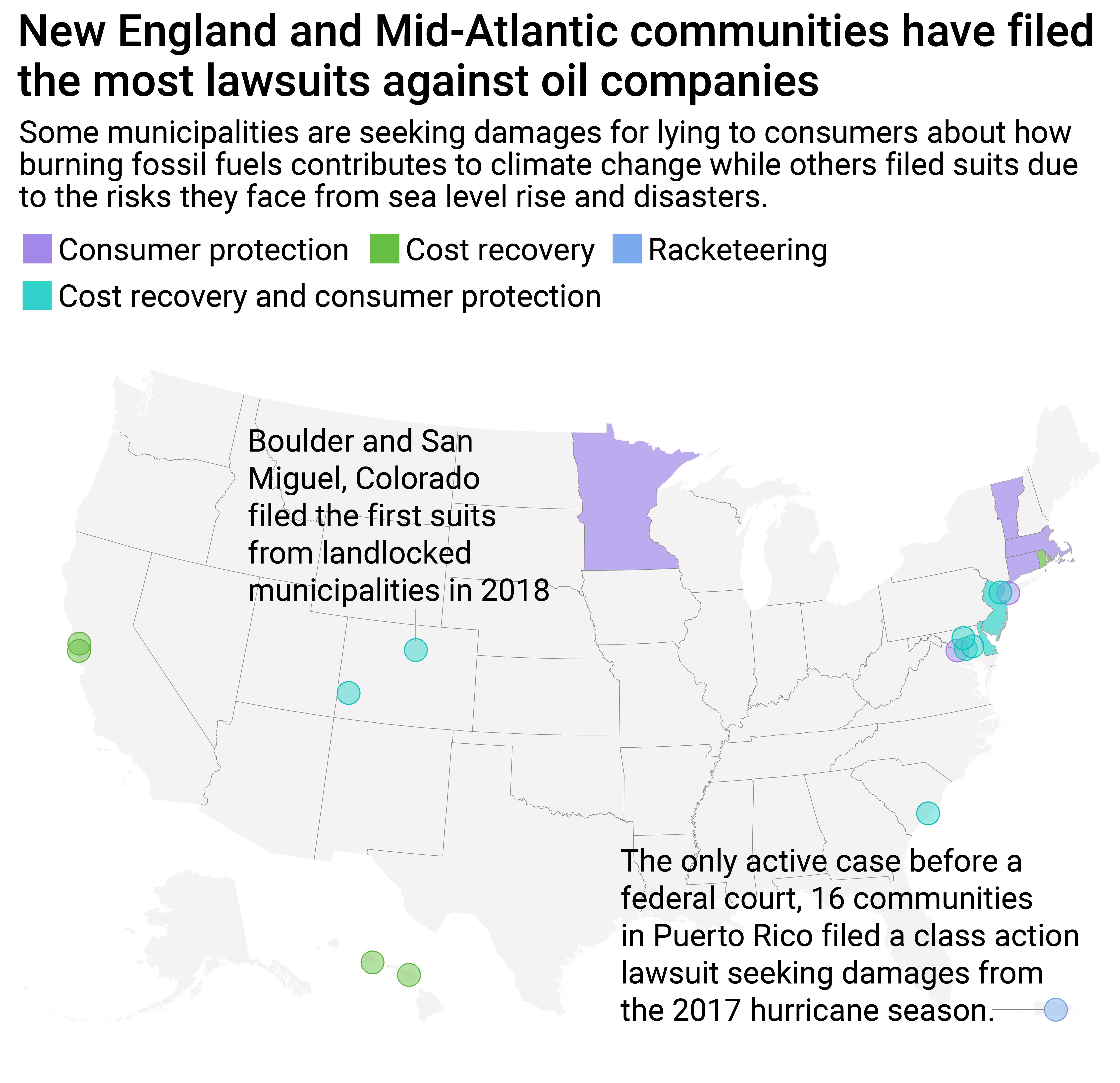

Coastal communities have filed most lawsuits

map showing states and local governments currently filing suits against oil companies.

Coastal communities have been most severely impacted by anthropogenic climate change, primarily due to rising sea levels.

Many coastal communities are also tourism-based economies, which suffer from climate-driven extreme weather events and infrastructural damage from rising seas. Coastal erosion is responsible for about $500 million in coastal property loss alone each year. Even landlocked states such as Colorado, with many municipalities dependent upon snow and water tourism, feel the impacts of climate change. Like those filed in Colorado, the majority of lawsuits filed by local governments along the East and West coasts are seeking to recover damage costs.

Canva

Consumer protection

Four oil rigs with a sunset in the background.

– State of Vermont: ExxonMobil, Shell, Sunoco, and CITGO

– New York City, New York: ExxonMobil, Shell, BP, and the American Petroleum Institute

– State of Connecticut: ExxonMobil

– Washington D.C.: ExxonMobil, BP, Chevron, and Shell

– State of Minnesota: ExxonMobil, Koch Industries, and the American Petroleum Institute

– Commonwealth of Massachusetts: ExxonMobil

Federal and state consumer protection laws protect consumers from unfair and deceptive business practices. States and cities filing consumer protection lawsuits allege that large oil companies engaged in deceptive practices, specifically failing to disclose what they knew from their own scientists about the extent to which fossil fuels contributed to climate change. The lawsuits allege that this deception amounts to fraud.

Canva

Cost recovery

A sea level rise indicator in Sydney Harbor.

– Maui, Hawaii: ExxonMobil, BP, Chevron, Shell, and other fossil fuel companies

– Honolulu, Hawaii: Over a dozen companies

– State of Rhode Island: ExxonMobil, Shell, Chevron, BP, and others

– Oakland and San Francisco, California: ExxonMobil, Chevron, Shell, BP, and ConocoPhillips

– Six California counties and cities: 36 oil companies

The cost recovery lawsuits involve suing the fossil fuel industry for damages resulting from climate change. Many seek to recover costs associated with infrastructure damage due to rising sea levels driven by greenhouse gas emissions. Maui’s lawsuit, for example, states that more than $3.2 billion in assets, including 3,100 acres of land, 760 structures critical to Maui’s tourism-based economy, such as hotels, and 11.2 miles of major roadways, are at risk of destruction because of sea level rise.

Canva

Cost recovery and consumer protection

Coastal flooding in Texas after Hurricane Alex.

– State of New Jersey: ExxonMobil, Chevron, Shell, BP, ConocoPhillips, and the American Petroleum Institute

– Anne Arundel County, Maryland: ExxonMobil, Chevron, Shell, BP, the American Petroleum Institute, and other companies

– Annapolis, Maryland: ExxonMobil, Chevron, Shell, BP, the American Petroleum Institute, and other companies

– State of Delaware: Over 30 oil companies

– Charleston, South Carolina: 24 oil companies

– Hoboken, New Jersey: ExxonMobil, Shell, BP, Chevron, ConocoPhillips, and the American Petroleum Institute

– Baltimore, Maryland: 26 companies

– Boulder, Colorado: ExxonMobil and Suncor Energy

– San Miguel, Colorado: ExxonMobil and Suncor Energy

In many cities and states, consumer protection violations and cost recovery go hand in hand, particularly those along the coasts, alleging deceitful tactics and damage sustained as a result. An economic analysis of the impacts of climate change on Delaware determined the cumulative potential economic impacts that could be realized by the year 2099 total $69 billion: approximately 80% of the state’s gross domestic product last year.

Canva

Racketeering

Large industrial oil tanks at sunset.

– 16 Puerto Rican municipalities: ExxonMobil, BP, Chevron, Shell, and other fossil fuel companies

Puerto Rico filed the first-ever climate change lawsuit focused on alleged racketeering. The suit alleges that major fossil fuel companies conspired to downplay the risks of their fossil fuel products and deceive the public about the direct link between their greenhouse gas-emitting products and climate change.

The lawsuit cites the creation of the Global Climate Coalition, formed in 1989, as a primary vehicle for launching deceptive marketing campaigns that are still active today. It also references the 1998 American Petroleum Institute Global Climate Science Communications Team Action Plan, in which representatives from Exxon, Chevron, Southern Company, and others note that victory can only be achieved when the American people recognize the “uncertainty” of climate science.

The suit also seeks to hold the fossil fuel companies financially responsible for damages from the devastating 2017 hurricane season, which researchers found was made worse by climate change.