Food insecurity is declining in the US, but for those with the least access to food, little has changed in 15 years

Ground Picture // Shutterstock

Food insecurity is declining in the US, but for those with the least access to food, little has changed in 15 years

Person handing food donation box.

More than 10% of American households—or nearly 14 million people—struggle with getting the food they need to live a healthy life, according to the most recent data from the Department of Agriculture.

Food insecurity, defined as not having access by all people in a household at all times to adequate, nutritious food, often reflects broader economic trends like recession and inflation. Roughly 5 million Americans experience “very low food security,” or limited access to food so severe that their consumption habits are changed, resulting often in smaller or missed meals.

Food insecurity hit an all-time high in the U.S. during the Great Recession. More than 50 million Americans lived in households that struggled with getting enough to eat at some point in 2009, including 17 million children. COVID-19 also drove up rates of food insecurity nationwide due to layoffs, social distancing measures, supply-chain-driven food shortages, and school closures. In the six months following the start of the pandemic in the U.S., Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, or SNAP, enrollment increased by nearly 5 million.

When looking at the larger trend, however, in conjunction with increased federal spending on programs, including SNAP; the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children, or WIC; and the National School Lunch Program, food insecurity has been steadily decreasing nationwide, on average.

Food insecurity rates vary from state to state due to different population characteristics and state-level policies. For example, not every state requires schools to participate in the NSLP. Several states, like Mississippi, Oklahoma, and Alabama, which do not require NSLP participation, have some of the highest numbers of eligible recipients. Regionally, food insecurity is more prevalent in the South.

Foothold Technology analyzed data from the USDA’s Economic Research Institute tracking food insecurity around the country. Data is compiled by the USDA from the annual Current Population Survey Food Security Supplement; it includes all 50 states and Washington D.C.

![]()

Foothold Technology

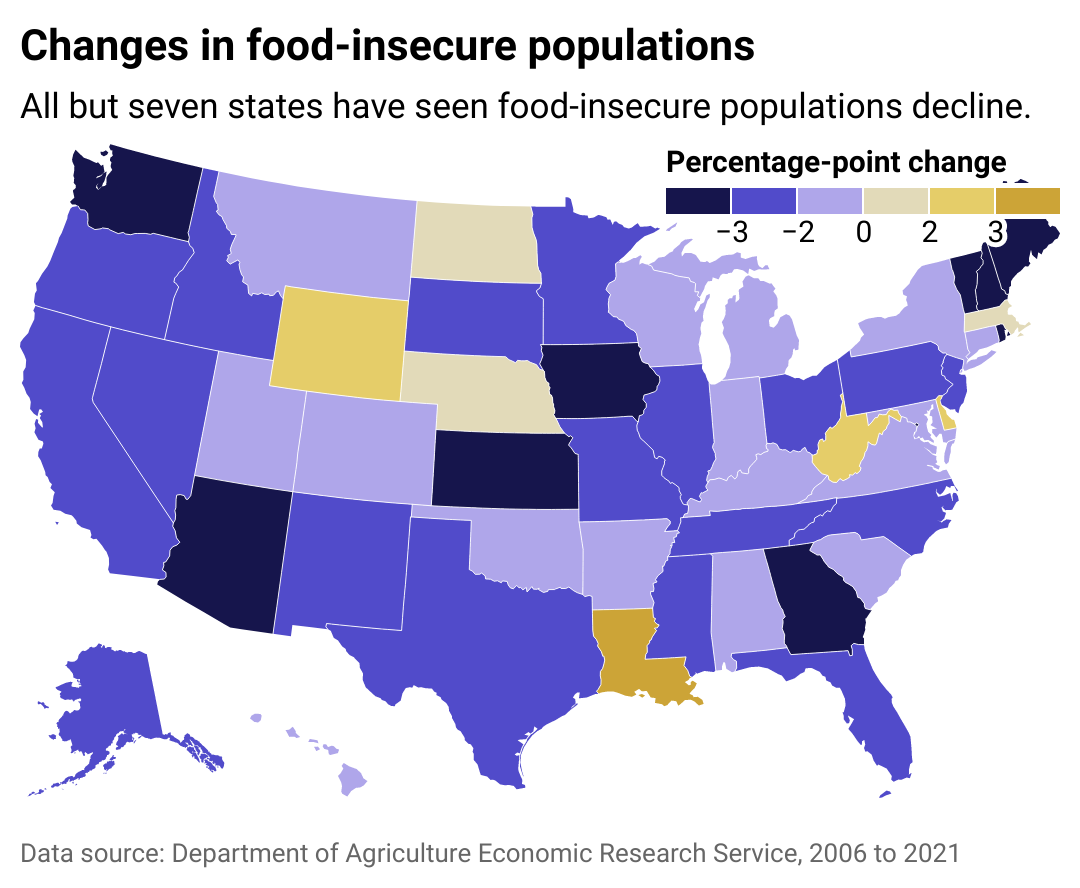

Federal assistance programs have had a positive effect on food-insecure populations

Map showing states changes insecure populations. Four states show an increase.

States with the greatest decline in food insecurity since 2006-08:

#1. Iowa: 7.0% (4.6-point decrease)

#2. Georgia: 9.9% (4.3 -point decrease)

#3. Vermont: 7.9% (4.2-point decrease)

#4. Maine: 9.5% (4.2-point decrease)

#5. Kansas: 10.2% (3.6-point decrease)

States with the greatest increase in food insecurity since 2006-08:

#51. Louisiana: 14.5% (3.5-point increase)

#50. Wyoming: 11.2% (2.0-point increase)

#49. West Virginia: 14.0% (2.0-point increase)

#48. Delaware: 11.2% (1.8-point increase)

#47. North Dakota: 7.7% (0.8-point increase)

SNAP, the largest federal food and nutrition assistance program, is also one of the most effective at combating food insecurity in the U.S. The program saw an increase in eligible recipients, applications, and utilization rate following the 2008 recession.

According to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, SNAP applications rose by 81% between 2007 and 2013 and have remained above pre-recession levels despite participation rates falling from their 2013 record high. This is largely because poverty rates do not rise and fall in lockstep with employment rates but tend to lag, meaning enrollment in federal assistance programs remains high.

However, as the country’s economy improves, SNAP enrollment generally decreases, reflecting more favorable individual economic conditions. Still, SNAP participation has dramatically improved over the last 20 years. Nationwide, 82% of the people eligible for SNAP received benefits, compared to a 54% participation rate in 2002.

Foothold Technology

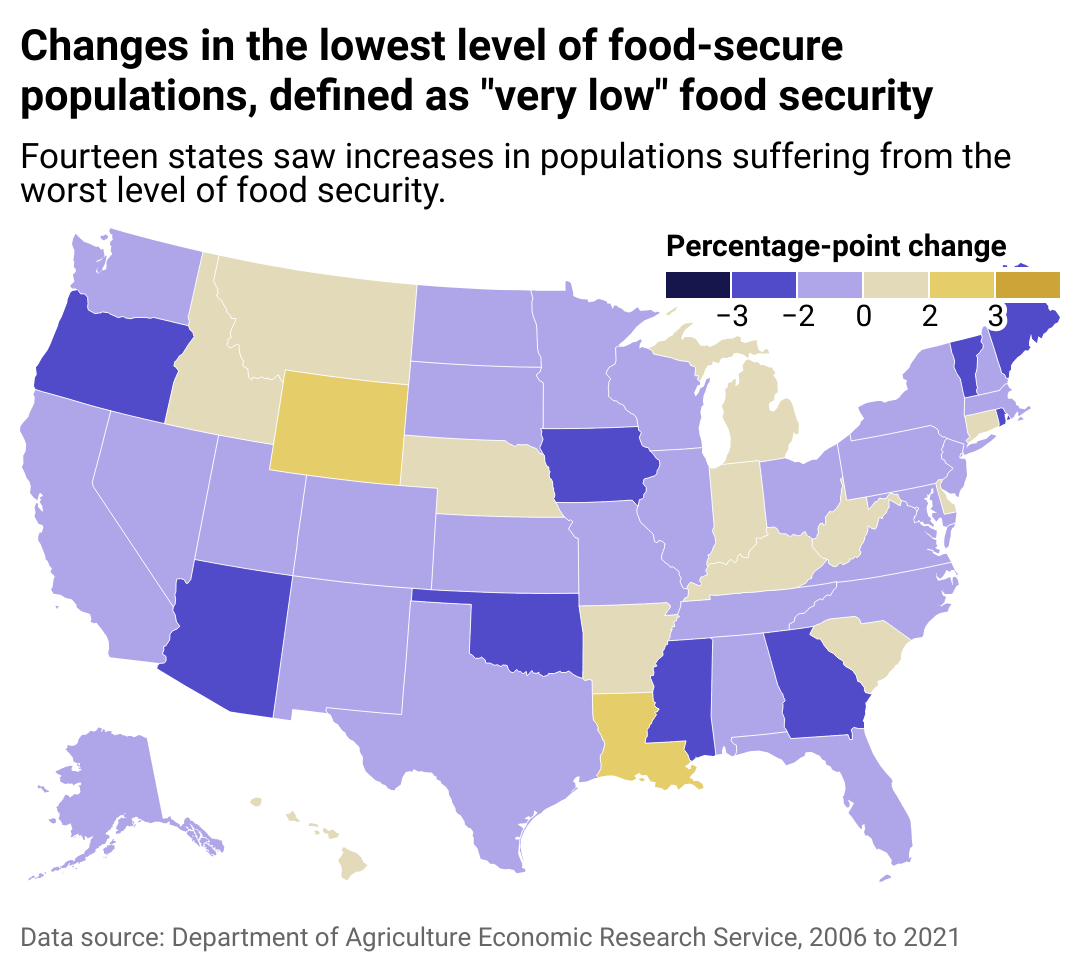

Despite the larger trend, the worst aspect of food insecurity has been on the rise

Map showing states changes in “very low” food security populations. Fourteen states show an increase.

States with the greatest decline in “very low” food security population since 2006-08:

#1. Vermont: 2.8% (2.9-point decrease)

#2. Oregon: 3.9% (2.7-point decrease)

#3. Iowa: 2.3% (2.5-point decrease)

#4. Maine: 4.5% (1.9-point decrease)

#5. Mississippi: 5.5% (1.9-point decrease)

States with the greatest increase “very low” food security population since 2006-08:

#51. Louisiana: 5.7% (2.0-point increase)

#50. Wyoming: 4.7% (1.8-point increase)

#49. South Carolina: 5.9% (0.7-point increase)

#48. West Virginia: 5.2% (0.7-point increase)

#47. Arkansas: 6.3% (0.7-point increase)

The top three states that have seen the most significant reduction in the number of people with very low food security over the last 15 years all have SNAP enrollment rates above the national average. In Oregon, for example, 100% of people eligible for SNAP benefits are enrolled in the program, compared to the national average of 82%.

Living below the federal poverty line is the most common characteristic of households facing food insecurity. Louisiana, West Virginia, and Arkansas, which saw rates of the most severe degree of food insecurity increase over time, are among the top five states with the greatest percentage of the population living in poverty. Louisiana also has the highest rate of food-insecure children of any state in the U.S.

Foothold Technology

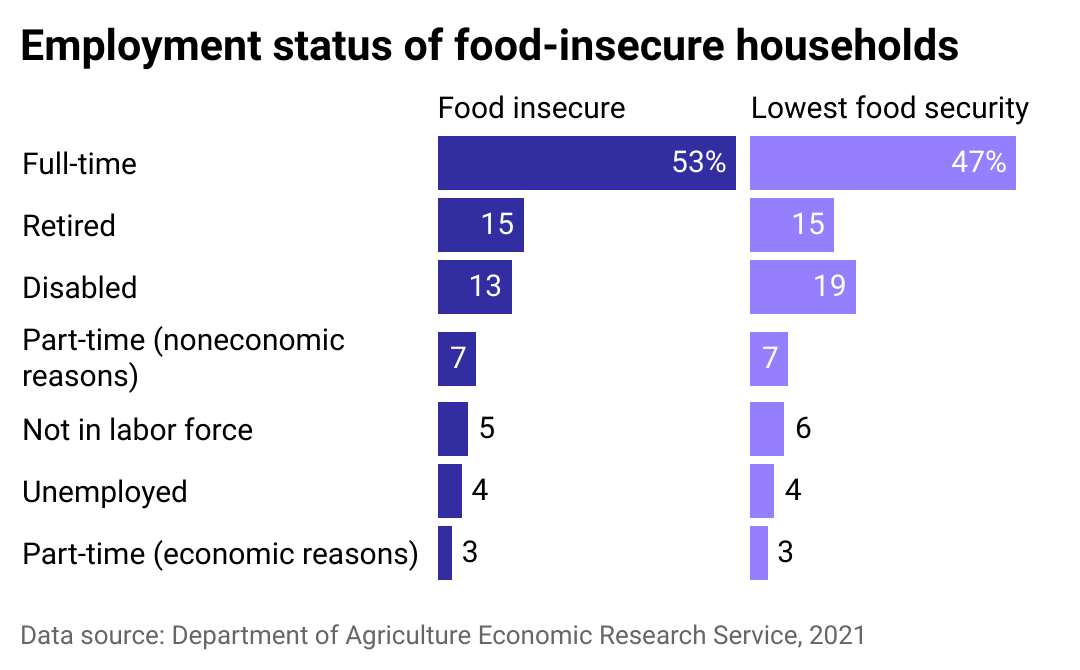

Half of food-insecure people are employed full-time

Bar chart showing employment demographics for food-insecure populations; 53% of food-insecure households are employed full-time.

Full-time employment does not guarantee food security, especially when the cost of living outpaces a person’s paycheck. Sometimes referred to as ALICE—Asset Limited, Income Constrained, Employed—these households live paycheck to paycheck, earning enough to put them above the federal poverty level but not enough to afford the bare essentials all at once, like housing, food, child care, health care, and transportation.

ALICE households may experience periods of food insecurity while money is constrained. Parents may skip meals to feed their children or buy fewer groceries to cover rent. While food insecurity and very low security are prevalent in households below the federal poverty level, they are also common among single-mother households that must juggle work, child care, and at-home responsibilities.

Retired populations are also vulnerable to food insecurity. Overcome by the generational stigma associated with accepting government assistance, adults over 60, largely representing the retired group, are less likely than younger adults to enroll in federal food and nutrition programs.

Foothold Technology

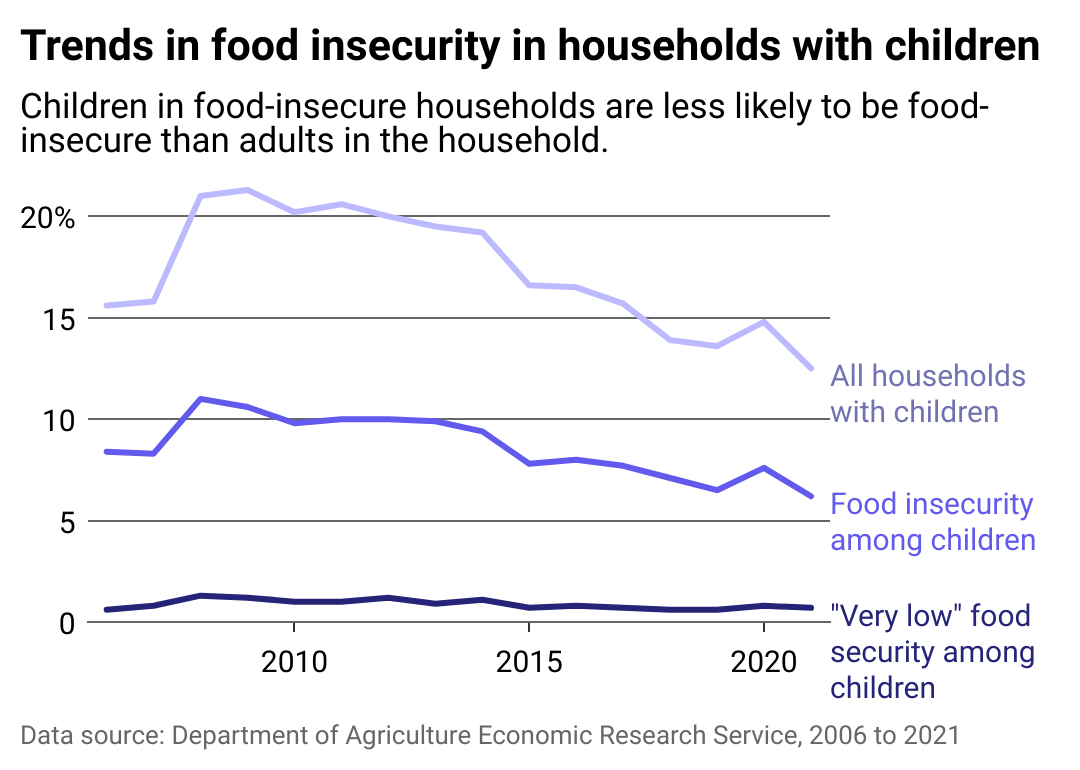

In food-insecure households with children, parents prioritize the children’s well-being over their own

Line chart showing trends in food insecurity among households with children generally declining. The children in these households experience less food insecurity than the adults.

Numerous studies have shown that parents in food-insecure households will go without meals so their children don’t have to, especially in homes with very low food security. In 2021, for example, more than 12% of U.S. households with children were food-insecure, but in half of those households, only the adults experienced food insecurity, according to the USDA.

Federal programs like SNAP, WIC, NSLP, and the School Breakfast Program, among others, are designed to ensure, as much as possible, children have access to adequate healthy food. Many children are also receiving assistance from more than one source. A 2021 report from the Census Bureau found that more than 9 in 10 children enrolled in SNAP were enrolled in at least one other federal assistance program; 1 in 3 children receiving SNAP are enrolled in at least three programs.

Despite these programs and parental sacrifice, households with Black and Hispanic children face significantly higher-than-average rates of food insecurity.

This story originally appeared on Foothold Technology and was produced and

distributed in partnership with Stacker Studio.