Ever-Bloom tries to clear the air

One of the largest and smelliest cannabis greenhouse projects in the Carpinteria Valley, a close neighbor of Carpinteria High School and a flashpoint in the local pot wars, was unanimously approved by the county Planning Commission this month, amid hopes that an emerging technology from the Netherlands will give residents some lasting relief from the “skunky” stench of pot.

The Feb. 2 vote in favor of zoning permits for Ever-Bloom, an 11-acre cannabis greenhouse operation owned by Ed Van Wingerden at 4701 Foothill Road, came on the heels of the commission’s unanimous approval on Jan. 12 of permits for Maximum Nursery, a four-acre cannabis greenhouse at 4555 Foothill, owned by Ed’s brother, Winfred Van Wingerden. Under the county’s permissive cannabis ordinance, both projects, like many others in the valley, have been allowed to operate without permits for more than four years.

In early 2020, the Santa Barbara Coalition for Responsible Cannabis, a countywide advocacy group, filed a public nuisance lawsuit against Ever-Bloom and Maximum. Between mid-2018 and last week, records show, Carpinteria residents have submitted 188 complaints to the county about the pungent smell of pot near Ever-Bloom and the soapy “laundromat” smell of the “misting” system that is supposed to neutralize it. They said the odors were driving them indoors and, in a few cases, causing breathing problems, headaches and stinging eyes.

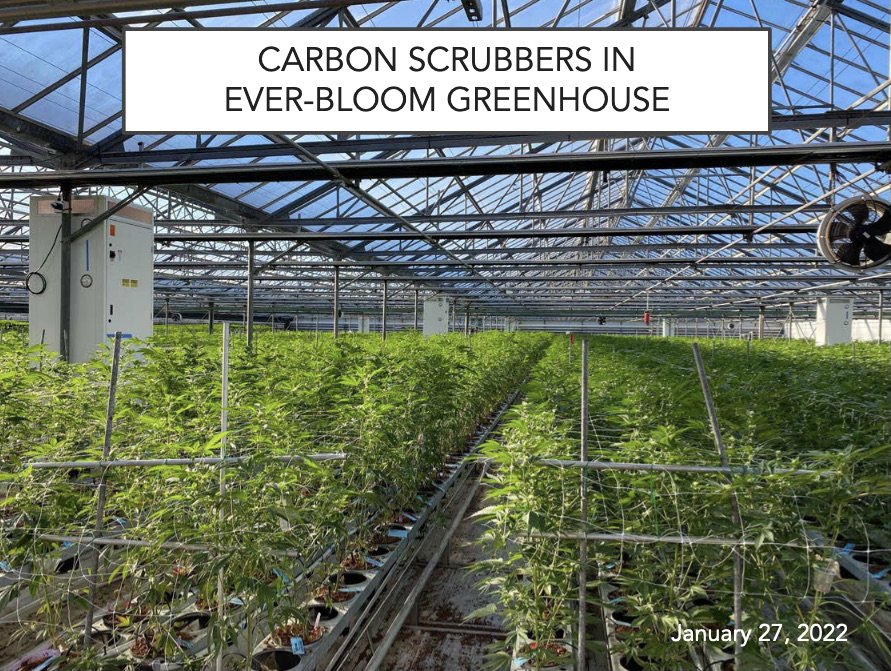

Now, the Van Wingerdens are heading up a drive to install the latest generation of air filters in valley greenhouses to get rid of the stink of cannabis in the small beachside community, where and the coalition’s lawsuit is on hold. Forty of these filters, called carbon “scrubbers,” are expected to arrive for Maximum in May, and more than 100 are currently under installation at Ever-Bloom, a $2 million investment.

The Dutch scrubbers have been shown in small-scale tests at a Carpinteria greenhouse to eliminate more than 80 percent of the smelly gases emitted by marijuana plants. A full-scale test of the new technology will begin at Ever-Bloom this month, Phil Greene, president of Ever-Bloom and Maximum, told the commission.

Greene has worked closely with Carpinteria growers for more than five years, testing odor control technologies. The goal at Ever-Bloom, he said, is to reduce the smell of cannabis inside the greenhouses so that it can’t be detected at the high school or in nearby residential neighborhoods.

“I’m confident that we’re on the right path as an industry and community to see drastic odor improvement in the coming months and year, as more and more farms adopt and implement the new technology,” Greene said.

School proximity

But members of Concerned Carpinterians, a loosely knit group of 300 people who advocate for stricter regulation of the cannabis industry, are not so confident. They said this week they would appeal to the county Board of Supervisors to overturn the commission’s decision and deny zoning permits for Ever-Bloom.

These critics contend that Ever-Bloom is growing marijuana too close to the high school, creating a health hazard for students with the smell of pot and sending the wrong message to young people about drug use. The northeastern corner of the greenhouse property is 360 feet from the school property line. The United Boys & Girls Clubs of Santa Barbara County and several elementary schools are located less than half a mile from Ever-Bloom.

“There are dozens of damaging cannabis grows in the county, but this one is the worst,” Annie Bardach, a valley resident, told the commission. “This is the one that keeps people up at night.”

In a provision that has benefited Ever-Bloom, county ordinances ban cannabis operations within 750 feet of schools — not measured property-line-to-property line, but from school property lines to the “premise” where cannabis is under cultivation. For nursery plants, which are scent-free, the setback is 600 feet. Under those rules, and by defining “premise” as the marijuana plants themselves, the commission was able to okay the cultivation of nursery plants within a portion of the northeastern corner at Everbloom.

(Under section entitled, “Access to the Cannabis Industry,” a 2020 county Grand Jury report on what was happening behind the scenes as the ordinance took shape said it was “most concerning” that one of the county supervisors accepted an invitation to tour a cannabis operation in early February, 2018 to talk about how to measure setbacks from schools. The day before the Feb. 6 board vote on the matter, the report states, the owner sent the board member an email arguing that setbacks should be measured from school property lines to the premises of a cannabis operation, and not from property line to property line, as the county Planning Commission was recommending. The board adopted the language that the grower wanted.)

At the commission hearing on Ever-Bloom this month, Bardach said the greenhouse was in violation of federal drug laws that allow stiffer sentences for the crime of distributing or manufacturing cannabis within 1,000 feet of a school.

“Would this ever be happening at any school with a majority white population?” Bardach asked, noting that more than half of the high school students were Hispanic.

But Callie Kim, deputy county counsel, told the commission, “I don’t have any concerns that there’s a violation of federal law … We’re in a gray area where federal law treats cannabis differently from state and local law, but that’s been the case for a long time now. The Planning Commission needs to make sure the project complies with local ordinances.”

In all, seven projects totaling 50 acres of cannabis have been approved or are under county review in the vicinity of Carpinteria High. Of the total, 38 acres are currently under cultivation. Most of Mediedibles, a three-acre “grow” at 4994 Foothill, along the school’s eastern boundary, lies within the 750- and 600-foot setbacks where the county has banned cultivation; and a portion of the five-acre “grow” at 4532 Foothill to the west of the school lies within the 750-foot setback.

Anna Carrillo, a member of the coalition and Concerned Carpinterians, said the growers operating around Carpinteria High should be required to hire an independent odor specialist to monitor the smell of cannabis twice a day at the school.

“Who is going to be in charge?” she asked.

Cannabis cash

The Van Wingerdens built their greenhouses in the 1980s just outside the city limits, creating a booming business in Gerbera daisies there. They pivoted to pot in 2016, after state voters legalized marijuana, and now they’re the leading cannabis growers in the valley.

At the hearings, a number of Carpinterians spoke or emailed letters in support of Maximum and Ever-Bloom; they said cannabis was providing good jobs and would save farmland from urban sprawl. Among these supporters were fellow farmers, employees of the cannabis industry, and representatives of organizations that have received donations from CARP Growers, an industry group. Winfred Van Wingerden is the founding president; he and Ed are two of 18 members with 21 cannabis greenhouse properties in the valley.

Sally Green, a Carpinteria Unified School District trustee who lives near Ever-Bloom, praised the Van Wingerdens as “generous donors to nonprofit organizations” and told the commission, “Cannabis odors have dramatically improved to where it is rare I smell anything … Ed and his family are problem solvers and exemplify the kind of farmer we want in Carpinteria.”

According to a spokesman for CARP Growers, the group has donated about $400,000 to local nonprofits during the past three years. Of that amount, $189,000 went to the district to cover the salary of a mental health and drug abuse counselor for Carpinteria Middle School for three years.

No one from the high school administration spoke at the Feb. 2 commission hearing. But Jay Hotchner, a teacher who is president of the Carpinteria Association of United School Employees, turned in the union’s 2019 survey of district faculty and staff concerning cannabis odors.

“Our district students and colleagues have consistently expressed concern about the negative impacts of cannabis production in such close proximity to our district schools and work facilities,” Hotchner said.

At the hearing’s end, Commissioner Michael Cooney, who represents the valley, tried to clarify that the Van Wingerdens’ philanthropy was “not our issue” and “not our focus.” Cooney said he had been a baseball coach at the high school for the past four years and had often smelled cannabis there. The new scrubbers, he said, “offer hope that nothing we’ve seen before can match.”

“The odor has been prevalent and frequent and irritating at times,” Cooney said, adding, “It doesn’t bother everybody, but it intensely bothers a number of people … I welcome the input from the teachers’ union. The odor problem is the issue for me that overwhelms all the rest”

The growers' promise

Last fall, the members of CARP Growers signed an agreement with the Coalition for Responsible Cannabis, their former adversary, pledging to implement “best available odor control technology” in their greenhouses, or risk coalition challenges to their permits.

To date, the county has approved permits for four cannabis operations that have pledged to install carbon scrubbers. In addition to Maximum and Evergreen, they are Cresco, a seven-acre operation at 3861 Foothill, and CVW Organic Farms, a 13-acre operation on Cravens Lane. (CVW’s owners, Cindy and David Van Wingerden, don’t belong to Carp Growers; they signed a separate agreement with the coalition and are using locally designed scrubbers.) The Dutch scrubbers were first tested in two acres of cannabis at Creekside greenhouses, owned by Winfred Van Wingerden at 3508 Via Real.

Together, these operations represent about 36 acres of greenhouse cannabis in the valley, out of 158 greenhouse acres that have been approved for permits to date. Most, like Ever-Bloom, have been under cultivation for more than four years. The county has placed a 186-acre cap on cannabis in the valley, a limit that will likely be reached this spring.

The Dutch scrubbers are being billed as replacements for some of the “misting” systems that are widely in use in Carpinteria’s cannabis greenhouses. These are pipes attached to the sides or roofs of greenhouses that emit a curtain of vapor — plant oils mixed with water — to neutralize the smell of cannabis in the outside air, after it has escaped out of the greenhouse vents. But many residents object to the perfumy smell of the mist itself.

It could take more than a year to install enough scrubbers to clean up the valley’s worst hot spots for the smell of pot. In the pandemic, there may be delays in manufacturing and shipping the scrubbers, and grower applications for electrical upgrades are already backed up at the county. Many growers may choose to lease, rather than buy, the scrubbers, which cost about $20,000 each. CARP Grower members who were granted permits without scrubbers may have to upgrade their operations. And not all of the growers in the valley are members of CARP Growers.

Up to now, cannabis odor complaints to the county — more than 2,100 since mid-2015 — have languished in limbo because no one could pinpoint which “grow” the smell was coming from. Under the agreement with the coalition, members of CARP Growers will field complaints directly; and they must fix the problem, even if it means monitoring the air, hiring an engineer and installing new technologies.

“This will hopefully help to alleviate that feeling that when someone complains, there is no followup with or pressure on the surrounding cannabis operations to respond,” Greene, the Ever-Bloom spokesman, said.

But for many Carpinterians, it’s not enough.

“I urge you to put a moratorium on any cannabis expansion until the applicants have a working odor control system that stops any odor from leaving their structures and property lines,” Paul Ekstrom, a plaintiff in the lawsuit against Ever-Bloom, wrote to the commission this month. “It is beyond my thinking that the neighbors and schools have to breathe the odors before the applicants have to prove they can be good neighbors.”

Melinda Burns, formerly of the Santa Barbara News-Press, is an investigative journalist with 40 years of experience covering immigration, water, science and the environment. As a community service, she offers her reports to multiple local publications, at the same time, for free.