On the frontlines: How nurses have responded in conflicts throughout history

U.S. Office of War Information/Library of Congress/Corbis/VCG via Getty Images

On the frontlines: How nurses have responded in conflicts throughout history

American Army nurses march in full war gear.

The first figures that come to mind as war heroes are undoubtedly soldiers. But oftentimes, it is easy to forget there are others working alongside them in war zones, though behind the scenes: nurses.

During World War I, over 22,000 professional nurses served in the Army, around half of whom deployed to the Western Front. This number rose to 59,000 during World War II, and there are nearly 30,000 nurses in the military today.

Nurses often face many of the same risks soldiers do: they routinely experience extreme stress, isolation, and physical danger while working in war zones and are at risk for PTSD once they return from deployment.

Throughout history, wartime nurses have left a legacy far broader than just saving lives. They have also used their positions to improve the quality of life in society as a whole. Many have blazed paths for racial equality—like Hazel W. Johnson-Brown, Mary Seacole, and Mabel Staupers, who all progressed the integration of Black women into the nursing profession.

Others have advanced education, including Anna Caroline Maxwell and Edith Louisa Cavell, who helped expand nursing education and establish it as a legitimate profession. Florence Nightingale helped advance medical practices by establishing sanitation standards. From the Crimean War to the Vietnam War to the Korean War and beyond, nurses have used their profession to advocate for advancements in health, education, gender equality, racial equity, and other sectors.

Incredible Health compiled a list of notable nurses who responded in conflicts throughout history using various news and historical sources. Read on to learn about the risks, obstacles, and innovations these women have made, from the Civil War up to today.

![]()

Bettmann // // Getty Images

Clara Barton

Clara Barton seated portrait.

Known as the “Florence Nightingale of America,” Clara Barton is best known for introducing the European-originated Red Cross to the United States. She served as a nurse on the frontlines in the Civil War, during which she mimicked the later duties of the Red Cross by traveling in ambulances to deliver care and supplies to victims and locate missing soldiers and contact their families. After learning about the Red Cross during travels in Switzerland post-war, she petitioned President Chester Arthur to permit an American branch, describing a wide-reaching organization that would tend to natural disaster victims as well as wartime casualties.

raymond orton // Shutterstock

Ruby Bradley

Military first aid kit.

After accumulating a remarkable 34 medals during World War II, Ruby Bradley became the most decorated army nurse in the U.S. military. She began in the Army Nurse Corps in 1934, before being captured and made a prisoner of war in the Philippines seven years later. While captive, she earned the moniker “Angel in Fatigues” for her irrepressible determination to provide aid and equipment to fellow prisoners, at great personal risk. Liberation only lasted for five years before Bradley headed back to the frontlines, serving as chief nurse of the 171st Medical Evacuation Hospital during the Korean War and continuing to provide lifesaving care to hundreds under dangerous conditions.

Ann Ronan Pictures/Print Collector // Getty Images

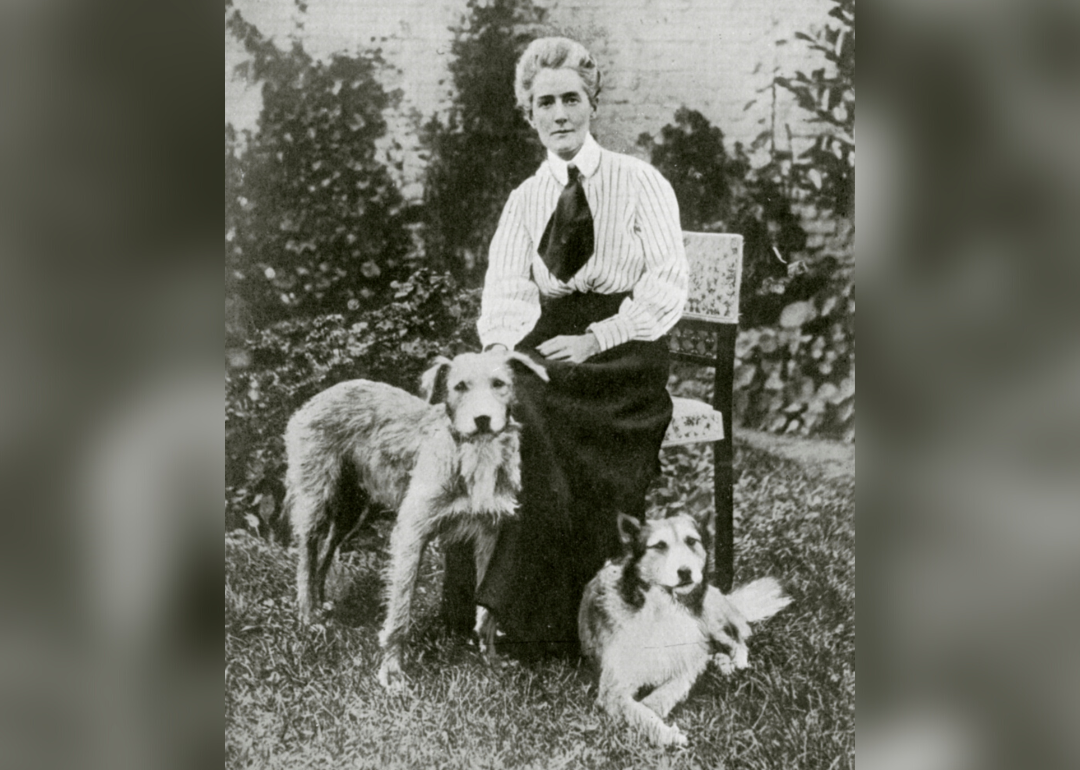

Edith Louisa Cavell

Edith Cavell with her pet dogs.

Many wartime nurses face great risk to serve at the frontlines, but Edith Louisa Cavell was actually tried and executed for her service. British-born Cavell studied nursing in the U.K. before becoming matron of the Berkendael Medical Institute in Brussels, spearheading efforts to create modern nursing education in the country. After World War I erupted and Germany invaded Belgium, the Institute was converted into a Red Cross hospital. Cavell was eventually arrested and confessed to treating at least 200 Allied soldiers and helping them escape to neutral Holland, a crime for which she was executed—while still wearing her nursing uniform.

Kean Collection/Archive Photos // Getty Images

Sarah Emma Edmondson

Portrait of Sarah Emma Edmonds.

Originally from New Brunswick, Canada, Sarah Emma Edmondson fled to New England to escape an abusive father. There, she was inspired to enlist in the Union Army during the Civil War—posing as a male army nurse named Franklin Flint Thompson. Under this disguise, she served as a nurse at the frontlines during some of the war’s bloodiest battles, including the Battle of Second Manassas and the Battle of Antietam. She eventually left the frontlines and continued working as a nurse—no longer disguised as a man—in hospitals through the end of the Civil War.

Dirck Halstead // Getty Images

Diane Carlson Evans

Diane Carlson Evans touches a monument by artist Glenna Goodacre.

It didn’t take long after Diane Carlson Evans graduated from nursing school in Minnesota to head out to the frontlines: At just 21, she joined the Army Nurse Corps and headed to the frontlines of the Vietnam War. She spent one year treating battle-wounded soldiers and, upon her return, spent many more years advocating for the recognition of women who had served in the war. She was struck by how the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, groundbreaking as it was, only listed eight women nurses and was heralded by a statue of three men. She spent seven years lobbying Congress for the creation of the Vietnam Women’s Memorial, which Evans still acts as president of today.

Lt. J W Brooke // Imperial War Museums via Getty Images

Helen Fairchild

Stretcher bearers carry a wounded man to safety at The Third Battle of Ypres.

When Helen Fairchild departed Pennsylvania Hospital for France during World War I as part of the American Expeditionary Force, she was stationed in one of the most grueling sites possible, treating soldiers at Casualty Clearing Station Four of the Battle of Ypres Passchendaele. Conditions for army nurses were so hazardous that Fairchild was routinely exposed to mustard gas and other lethal materials. She soon developed a large gastric ulcer and died from complications from surgery only nine months after her deployment to Europe. Although Fairchild’s military career was short, her legacy has inspired many army nurses, as her prolific letter correspondence from the frontlines has preserved her experiences beyond her generation.

Craig Herndon // The Washington Post via Getty Images

Hazel Johnson-Brown

Hazel Johnson-Brown seated at desk.

It was a rejection that spurred much of Hazel Johnson-Brown’s success, as rejection from the West Chester School of Nursing for being Black led her to attend nursing school in New York instead, join the Army Nurse Corps, and rise to the role of brigadier general. She was the first African American person to hold the prestigious role, during which she oversaw 7,000 individuals in the Army National Guard and Army Reserves, as well as an international network of medical centers and hospitals. After her time at the frontlines, Brig. Gen. Johnson-Brown worked as a professor of nursing at Georgetown University and helped found George Mason University’s Center for Health Policy.

mark reinstein // Shutterstock

Anna Caroline Maxwell

Tombstone of Anna Caroline Maxwell at Arlington National Cemetery.

Many of the nurses on this list rose to prominence through their work within the Army Nurse Corps, which Anna Caroline Maxwell founded. Maxwell was a highly educated and accomplished nurse in her own right, holding leadership positions at the Boston Training School for Nurses, St. Luke’s Hospital, the New York City Presbyterian Hospital, and Columbia University. Once the Spanish-American War unfolded, Maxwell’s expertise was indispensable in treating soldiers at the frontlines, where only 67 died under her care. She later petitioned Congress to establish the Army Nurse Corps in 1901 and went on to serve as an active-duty nurse again during World War I. Thanks to Maxwell, nursing education, procedures, and recognition as a profession advanced significantly.

London Stereoscopic Company/Hulton Archive // Getty Images

Florence Nightingale

Florence Nightingale seated portrait.

Perhaps no nurse is more well-known than Florence Nightingale, the “founder of modern nursing.” During the Crimean War, Nightingale realized that conditions within medical centers were more lethal for soldiers than the battlefields themselves due to poor hygiene. She instituted practices that are now foundational to every medical institution, including hand-washing and using sanitizing equipment. She went on to advocate for the recognition of nursing as a legitimate profession and founded the first professional school of nursing in the world.

Patryk Kosmider // Shutterstock

Margie Oppenheimer

Barbed wire fence at Majdanek concentration camp.

German-born Margie Oppenheimer and her family were captured and deported to a concentration camp during the Holocaust in 1938. Over the coming years, as Oppenheimer moved between concentration camps in Latvia, Poland, and Germany, she worked as a nurse in the camps, under traumatizing conditions, and without any tools or medications. Despite this, she continued to work as a nurse for years after her release from the camps, eventually moving to the United States and becoming licensed in Illinois.

Bruno Vincent // Getty Images

Mary Seacole

A historian holds a portrait of Mary Seacole by Albert Challen.

Mary Seacole, a free Black woman born in Jamaica, never attended formal nursing school, instead picking up a combination of her mother’s traditional herbal methods and European treatment styles from visiting soldiers. When the Crimean War broke out, Seacole was determined to serve as a military nurse but was rejected at least four times because of her race. Determined, she instead raised her own funds to travel to Crimea, where she used her unique treatment practices to tend to British soldiers, paving the way for future women of color to make their way to the frontlines as well.

Archive Photos // Getty Images

Mabel Staupers

United States Army nurses during a lecture in a classroom.

Mabel Staupers’ experiences as a nurse showed her just how segregated the health care world was at a time when equity was needed most. By World War II, Staupers had graduated from Freedmen’s Hospital School of Nursing and worked as executive secretary for the Harlem Tuberculosis Committee, a role that showed her the clear divide between the treatment Black and white people—nurses and patients alike—received in hospitals. She then became executive secretary of the National Association of Colored Graduate Nurses, spending over a decade there working to integrate Black nurses into the wider field, both in military and civilian medical institutions. Thanks to her advocacy, the Army Nurse Corps became desegregated after the bombing of Pearl Harbor.

Universal History Archive // Universal Images Group via Getty Images

Susie Baker King Taylor

Susie Baker King Taylor portrait.

Susie Baker King Taylor was born to enslaved people but was freed by their enslaver as a child. She later married an officer in the U.S. Colored Infantry Regiment during the Civil War and began working as a nurse (and laundry woman) for the regiment. She wrote about her experiences tending to Black soldiers in her memoir “Reminiscences of My Life in Camp with the 33d United States Colored Troops, Late 1st S.C. Volunteers,” making her the first—and only—African American woman to document her experience during the Civil War.

MPI // Getty Images

Sojourner Truth

Sojourner Truth portrait.

Sojourner Truth is best remembered as a trailblazer for the abolition of slavery, but before she was freed, she worked as an enslaved nurse. She first built up her skills while serving as a nurse for a family in New York; once free, she treated Black soldiers during the Civil War. After the war, she lobbied for the nursing profession alongside advocating for women’s rights and the end of slavery. Through the National Freedman’s Relief Association in Washington D.C., she petitioned the government to establish nursing education and training for freed women like herself.

This story originally appeared on Incredible Health and was produced and

distributed in partnership with Stacker Studio.