How weather has shaped human history

Public Domain // Wikimedia Commons

How weather has shaped human history

Weather has influenced significant events thorughout human history, whether forced migration or the course of a war.

Sometimes these events are tied to climate change, other times they represent anomalies that affected the future of air travel or launched eras of famine and disease. In the forthcoming list, Stacker examines dozens of ways weather has shaped human history, drawing on historical documents, newspaper articles, first-person accounts, and documented weather events.

Chinese scientist Shen Kuo was the first person to study climate. In his 1088 “Dream Pool Essays,” he ponders climate change after finding petrified bamboo in a habitat that wouldn’t support such growth in his lifetime. Since then, inventions and technological advances have allowed people to track the weather over time and, in some instances, even control it.

Around 1602, Galileo was the first to conceptualize a thermometer that could quantify temperature, allowing people to track changes in heat. The air conditioner made its first appearance in 1902; and in 1974 the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations held a classified briefing on the results of Operation Popeye, a five-year cloud-seeding experiment designed to lengthen Vietnam’s monsoon season, destabilize enemy forces there, and allow the U.S. to win the war.

But far more often than humanity seeks to control the weather, the weather does the controlling.

While weather refers to short-term atmospheric conditions (think of a forecast for how sunny and warm it will be next week), climate refers to long-term changes in overall weather trends over time (decades or hundreds of years). The two are impacted by each other. Climate change affects the severity and frequency of weather events, and the costs of extreme weather events rise as the effects of climate change become more apparent. With increased technology allowing for the tracking of weather trends over time and the anticipation and identification of potential weather hazards, people have been able to avert and prepare for some of nature’s wildest expressions.

Keep reading to find out what event kicked off the Salem Witch Trials, a new clue in the JFK assassination, and how a heavy storm thwarted the end of the Iran hostage crisis in 1980.

You may also like: Notable weather events from the year you were born

![]()

Internet Archive Book Images // Flickr

Climate change drives people out of Africa

There is no greater decider of human history than climate change, due to its long-term effect on weather conditions. The first and only example in this gallery of sustained climate change is here: it initiated the dispersal of people from Africa into other parts of the world.

Using modern-day computer modeling, scientists have discovered that humanity’s earliest push out of Africa and into other reaches of the planet was most likely due to changing long-term weather patterns. In a September 2016 report in Nature, authors Axel Timmermann and Tobias Friedrich explore how strengthened monsoonal climates and wet conditions throughout the Arabian and Sinai peninsulas created clear migration paths laden with natural resources that opened and closed at different points in history—and that line up perfectly with evidence of human dispersal. Other migration patterns, such as those into north Asia, similarly line up with decreasing amounts of glaciers roughly 20,000 years ago.

Public Domain // Wikimedia Commons

541: Drought leads to first recorded bubonic plague

The first recorded bubonic plague epidemic arrived in the mid-sixth century and resulted in an estimated 25 million deaths (50 million, when you include its two centuries of recurrence), accounting for roughly half of all people living at the time in the Roman Empire and toppling balances of power across the globe.

Scientists point to a period of extreme droughts and colder temperatures in Africa during the 530s as the bubonic plague’s cause. The lack of rain destroyed crops, which in turn depleted the population of small rodents that fed on those plants. The reduced number of these small rodents affected animals higher up the food chain, and populations of larger animals took longer than the vegetation to spring back when high levels of rain ended the drought; this lack of predators led small rodents to then populate in high numbers.

The influx of rodents infested East Africa and inevitably found their way to merchant ships bound for Europe and elsewhere. Many rats, gerbils, and mice also had fleas, which can carry a bacterium called Yersinia pestis. When rodent flea hosts died, the tiny bugs hopped to human hosts, infecting millions. Today, the plague still exists—but it’s easy to treat with antibiotics.

Daniel Schwen // Wikimedia Commons

900: Drought spells the end for Mayan civilization

During its peak around 800 AD, the Mayan civilization was responsible for awe-inspiring stone temples, almost four dozen cities, highly advanced astronomical observatories, and advances in mathematics and calendar-keeping that were far ahead of its time. Mayans also practiced slash-and-burn agriculture, which involves clear-cutting forests to grow land, then burning the vegetation that remains and moving onto a new plot. This method led to extreme deforestation in the Yucatan peninsula, a region that depended on root systems to maintain water tables after rainfall, its chief water source.

In a study published in Science in 2018, researchers found that, over 200 years, rainfall in the Yucatan peninsula dropped by as much as 70%. The extreme drought would have devastated any agriculture, turned dirt to desert, and made it impossible to survive if people stayed in their cities. The drought, combined with warfare, civil unrest, and other conflicts, spelled the end of the Mayan civilization. The Mayans themselves left behind a clue of how dire things had become. Among the ruins that thousands of tourists flock to each year are many carved stones in the shape of “Chaac,” the rain god of the Mayan culture.

Araniko // Wikimedia Commons

1274: Kublai Khan and the Kamikaze

The weather thwarted Mongol fleets attempting to attack Japan in 1274 and 1281.

Genghis Khan’s grandson Kublai Khan led both conquests, each of which was comprised of more than 4,000 ships with an army of 140,000 men, representing the largest-scale attempt of a naval invasion at that time (usurped only by the D-Day invasion in Normandy in 1944). Each attempt to overtake Japan failed epically because of typhoons, which the Japanese called “kamikaze,” or “divine wind.”

One of the ships from the 13th-century invasions was discovered in 2015 at the bottom of the ocean off the southern coast of Japan.

Charles Blomfield // Wikimedia Commons

1315: Extreme weather spawns the Great Famine of 1315-1317

Harsh winters, unseasonably cold summers, and heavy rains blanketed Europe between 1315 and 1317, decimating agriculture and spreading disease that was exacerbated by malnutrition from reduced access to fresh food. The Great Famine was marked by an extremely wet spring and summer that destroyed crops, prevented grain from ripening, and caused the price of salt—the only way to cure meat at the time—to skyrocket as brine could not properly evaporate. Bread became a luxury only afforded by the wealthy. Millions died in the years that followed from starvation, rampant disease, infanticide, and even cannibalism. Agriculture in the region wasn’t righted for a full decade, and the famine had dire consequences on European society, government, and the church.

Some blame the abnormal weather patterns on a massive volcanic eruption at Mount Tarawera in New Zealand in 1315 that lasted for five years. Ash from the eruption would have wreaked havoc on temperature patterns around the globe.

Tiziano Vecelli // Wikimedia Commons

1588: The wind flubs the Spanish Armada’s attack on England

In 1588, King Philip of Spain sent the Spanish Armada to invade England. Dropping anchor for the night, the fleet discovered unmanned, burning English ships floating toward them in the pitch black. The wind proved favorable for the English, who sent the ships they’d torched directly toward the Spanish—many of whom cut their anchor lines to get away.

Later, while traveling into the North Sea, the English were low on gunpowder and took harbor along the English coast. Unable to sail into the wind, through the English ships and on to Spain, the Spanish fleet continued north around Scotland. But with low food and water rations and many injured and sick sailors, the Spanish fleet resorted to starvation rations before running head-on into a heavy storm. Typically, ships would drop anchor to wait out the storm; however, many of the Spanish ships were traveling now without their anchors. Twenty-six of them smashed into the rocky Irish coast, killing close to 6,000 Spanish sailors and sparing England.

Sergei Vasilyevich Ivanov // Wikimedia Commons

1601: Volcanic eruption in Peru causes famine during Russia’s “Time of Troubles”

Before its eruption, the Huaynaputina volcano was thought to be a low Peruvian ridge. The deceptive crater packed a serious punch, spewing more than 7 cubic miles of ash and lava and causing a famine in Russia from 1601 to 1603 during the country’s “Time of Troubles.” 1601 became the coldest year in six centuries, and its effects on agriculture and health contributed to the deaths of 2 million people—a full one-third of the country’s population.

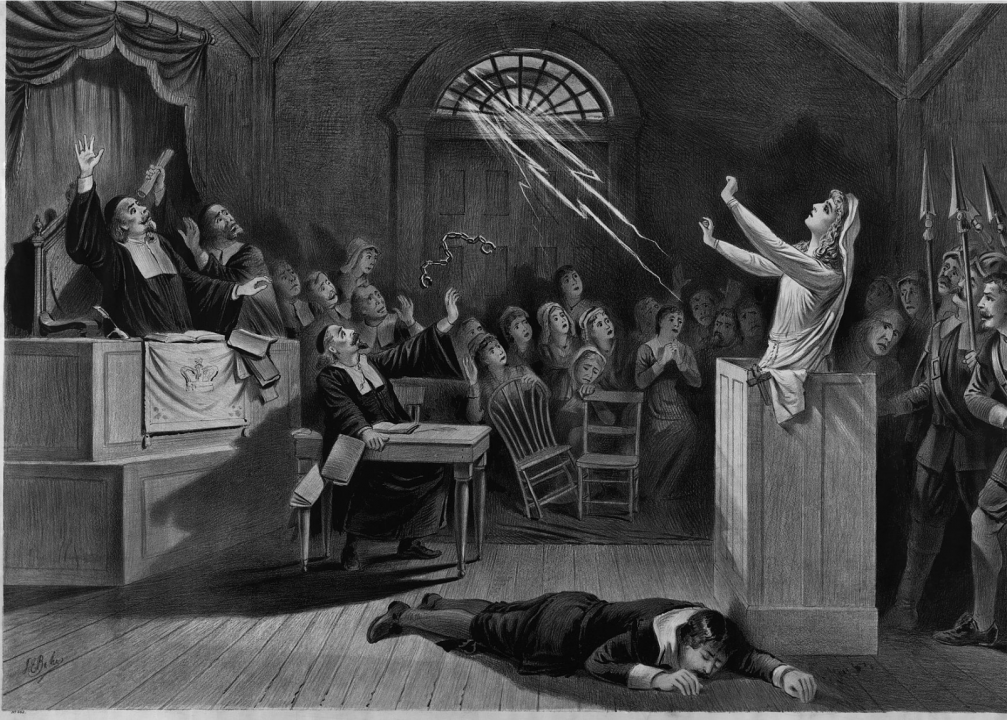

Baker, Joseph E // Wikimedia Commons

1692: Mini ice age instigates the Salem Witch Trials

The famous Salem Witch Trials between 1692 and 1693 ultimately resulted in more than 200 people being accused of practicing witchcraft and 20 people being put to death. Causes for the hysteria have been attributed to everything from socioeconomic issues in Salem to cold weather, which does overlap with periods of witch hunts throughout history.

The little ice age theory, laid out in 2004 by a graduate student at Harvard, contends that people thought witches could control the weather (and therefore could destroy food accessibility). Indeed, lower temperatures throughout the U.S. and Europe during a 400-year “little ice age” between the 1500s and 1800s also correspond to an uptick in accusations of witchcraft. The coldest period of this miniature ice age came between 1680 and 1730 and would have caused extensive hardship. Several diaries and even church sermons from this time suggest the bad weather helped to inspire the allegations.

James Charles Armytage // Wikimedia Commons

1776: Fog saves the American Revolution

By the summer of 1776, Britain had increased its troop strength on Staten Island to more than 30,000 in a battle against Gen. George Washington’s 19,000-man army for control of New York City. Half of the revolutionaries remained in Manhattan while Washington moved the rest out to Brooklyn and Queens, where British soldiers began their attack on Aug. 27. Americans stealthily made their way across the East River to Manhattan, totally undetected by the British soldiers just a few hundred yards away because of a dense fog cover.

Historians widely agree that Washington would have surely been captured and hung as a traitor while his army was overrun had it not been for that fog. Instead, the American Revolution ended in victory for the new colonies and the Treaty of Paris, which officially made the United States an independent nation.

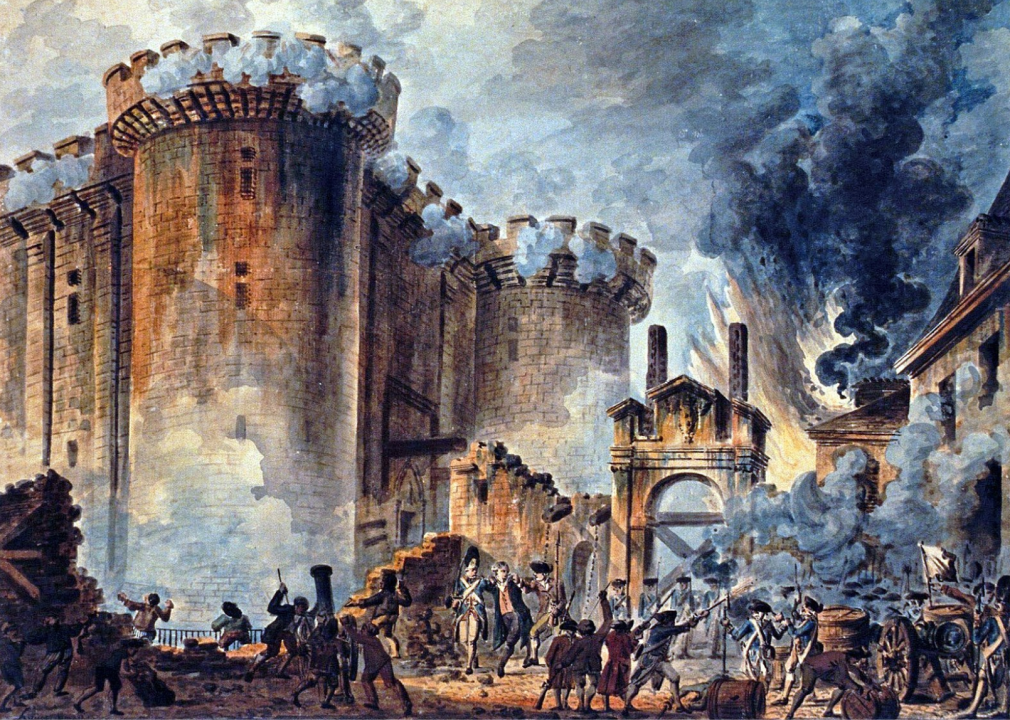

Jean-Pierre Houël // Wikimedia Commons

1789: The witch trials’ ‘little ice age’ also spurs the French Revolution

The same miniature ice age that contributed to accusations of witchcraft in Salem, Massachusetts, and throughout Europe also contributed to rising discontent in France. Colder temperatures throughout Europe and the United States, along with a 1783 volcanic eruption in Iceland and a band of warm ocean water in the central Pacific Ocean, resulted in widespread crop failures and drought across Europe.

In France, people were already strapped by taxes, which had been raised to support the American Revolution against the British Empire. The economic downturn and ravaged agriculture came to a head in 1788, when very heavy rains and hailstorms destroyed that year’s grain harvest and decimated crops. The upheaval led straight to the storming of the Bastille—Paris’ armory and political prison that served as a symbol of the monarchy’s corruption—in 1789.

Eyre Crowe // Wikimedia Commons

1800: Slave revolt is squashed by storms

Enslaved blacksmith Gabriel (known as Gabriel Prosser, with the last name of enslaver Thomas Prosser) was a literate blacksmith born into slavery in 1776 at a tobacco plantation in Henrico County, Virginia, called Brookfield. Gabriel planned a thousands-strong slave revolt for Aug. 30, 1800. His plan was to lead the enslaved individuals to Richmond, take over the city’s armory, and free everyone. Heavy rains caused a postponement of the revolt, which gave suspicious enslavers a chance to ply information about Gabriel’s plans and warn Virginia Gov. James Monroe, who sent in the state militia.

Gabriel was captured in Norfolk, where he had fled; he was turned in by a fellow enslaved man who did not receive the entire reward promised by the state. Gabriel would not submit to questioning in Richmond and was hanged along with his two brothers and 23 fellow enslaved people.

B. Villevalde // Wikimedia Commons

1812: Russian winter bests Napoleon

Russian winters are known for being fierce and have overwhelmed a number of armies over the years (two of which are featured in this gallery). One of the most famous instances of that unforgiving weather came in 1812 when Napoleon rounded up over 600,000 men to invade Russia so the country could be absorbed into his empire. Frigid temperatures hitting -22 degrees Fahrenheit blew after Napoleon’s men had already taken Moscow, killing upwards of 50,000 horses in one day. Only 25% of his soldiers made it out of the cold and back to France, marking a turn in Napoleon’s empire and the rise of Russia in Europe.

Napoleon’s final defeat came three years later in the Battle of Waterloo when heavy rains created excessive mud that wreaked havoc with the French emperor’s cannonballs and other offensive attempts.

William Emmons // Wikimedia Commons

1813: Tecumseh killed in the fog in the Battle of the Thames

Shawnee war chief, field commander, and leader Tecumseh was born around 1768 in Ohio. He organized a Pan-Indian federation intended to bring indigenous communities throughout the Great Lakes and Mississippi Valley together in preserving their cultures and rights against encroaching settlers. He also fought tirelessly for his people, traveling as far south as the Gulf of Mexico and north into Canada to promote his ideas. His territory of 100,000 people was up against 7 million settlers in the United States, but Tecumseh’s work nevertheless had people worried. He fought with the British in the War of 1812 against the United States, successfully taking over Detroit and overrunning enemy forts.

Tecumseh and 600 other warriors fought for six days in Moraviantown in what is now known as the Battle of the Thames, finally hiding in some swamps as the intense fog rolled in. More fighting ensued in low visibility, and Tecumseh was never seen again. He was presumably killed or captured, but the fog covered up what happened—and contributed to the United States’ consolidation of control over native lands throughout the Midwest and Northwest.

NASA // Wikimedia Commons

1816: ‘The Year Without a Summer’ creates America’s Heartland

Climate abnormalities in 1816 dropped the global temperature by 0.7 to 1.3 degrees Fahrenheit, wreaking havoc on crops across the Northern Hemisphere and creating massive food shortages. In addition to being on the tail end of the tiny ice age that had already caused so much global upheaval, a 10-day eruption of Mount Tambora in what is now Indonesia in 1815 shot high volumes of volcanic ash out into the upper atmosphere, carried everywhere by the jet stream and causing even colder weather.

Without a way to make ends meet, thousands of Americans left New England in 1816 and headed into the Northwest Territory (now the Midwest) and what is now western and central New York. In this way, “The Year Without a Summer” inspired the push west: Indiana became a state this year, followed by Illinois in 1818.

Willoughby Wallace Hooper // Wikimedia Commons

1876: Famines form the ‘Third World’

The term “Third World” was created during the Cold War to refer to development gaps across the globe due to income disparities and access. Many of these differences were most acutely shaped in the last quarter of the 1800s, particularly in 1876 when famines caused by El Niño drought brought utter destruction to crops in India’s Deccan Plateau, across China, and in Brazil, Ethiopia, and other parts of the world.

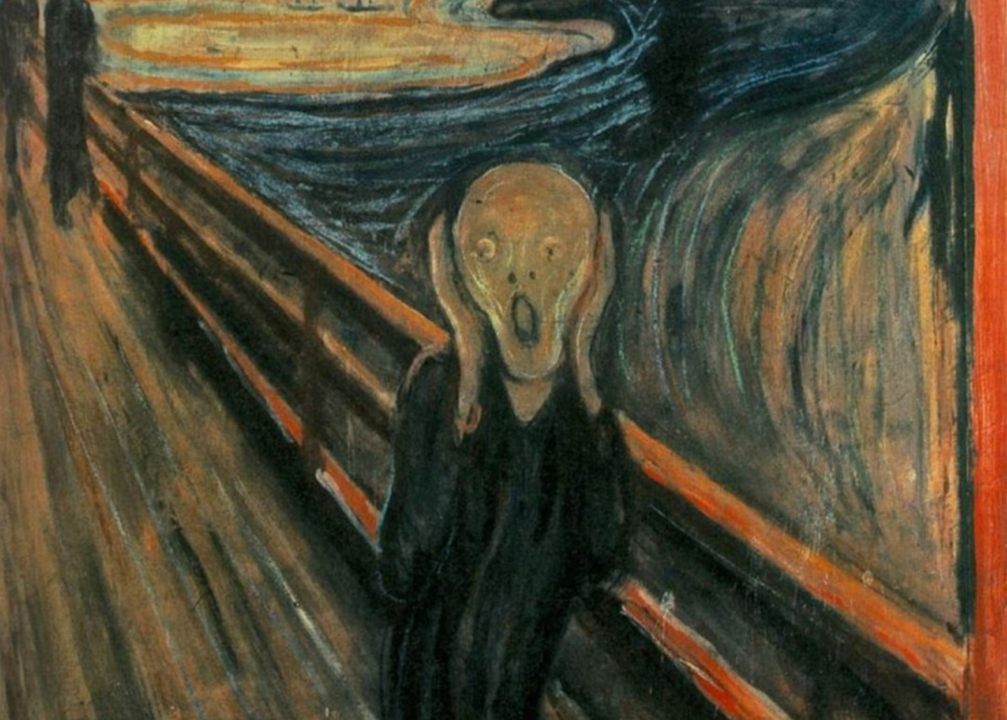

National Gallery of Norway // Wikimedia Commons

1893: Weather inspires painting of ‘The Scream’

One of the most famous pieces of art in the world may have been inspired by a bizarre weather event. A 2018 report published in the Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society posits that Edvard Munch’s skies depicted in his 1893 painting “The Scream” may actually be showing nacreous clouds, unusual and odd-looking formations that stretch across the sky and are filled with dark and varying colors just like those Munch painted.

National Archives and Records Administration // Wikimedia Commons

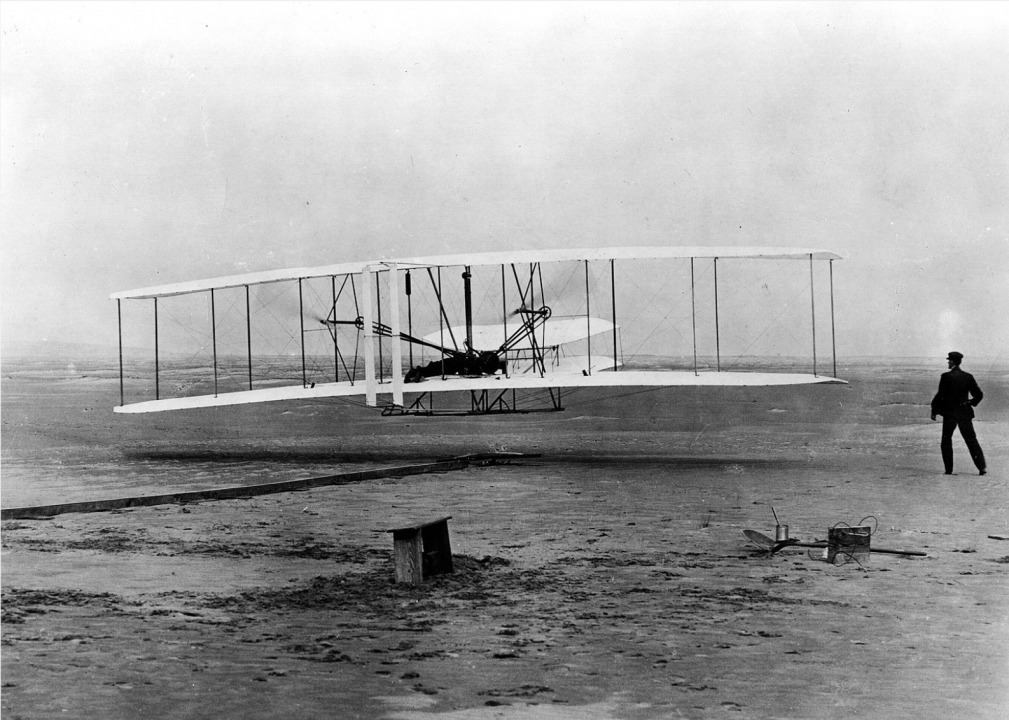

1903: Wind leads to an undocumented first flight

There’s a reason no one from the press was around to see the Wright brothers embark on the first airplane ride in 1903.

Nine days earlier, on Dec. 8, members of the media, Congress, and many others showed up to watch aviator Samuel P. Langley show off his heavier-than-air flying machine, which was pulled—along with its pilot, Charles Manley—onto a houseboat on the Potomac River and directed into the wind. The pins were released, which should have allowed a catapult to launch the apparatus into the air. Instead, a burst of wind caused the platform to buckle, the machine’s wings to break, and the entire aircraft to fall into the river. It was the second day in a row of failures for Langley’s great experiment, taking the proverbial air out of the otherwise rising excitement around air travel.

Willy Stöwer // Wikimedia Commons

1912: The Titanic sinks

There are a number of well-documented reasons for the sinking of the ill-fated Titanic and subsequent casualties numbering 1,503: an insufficient number of life vests or life rafts, too much speed, an utter dismissal of a whopping six ice warnings the day of the fateful crash, and course deviation for the sake of reaching New York sooner (just to name a few).

But nothing affected it so much as the weather.

After days of mild weather, the final night of the Titanic’s voyage was met with a cold front that dropped temperatures to around freezing just as the ship came into an Arctic high-pressure zone. There was no moon out, cutting visibility down significantly as a northwest burst of air behind the cold front pushed record tides—and a field of ice—toward the Titanic. The ocean where the crash occurred was estimated to be 28 degrees that night, with its freezing point lowered because of the ocean’s salt content.

NOAA George E. Marsh Album // Wikimedia Commons

1930s: The Dust Bowl

The hazards of unsustainable agriculture weren’t only learned by the Mayans; the Dust Bowl of the 1930s also brought lessons in what happens when biodynamic farming principles go unfollowed.

In the Great Plains, native grasses are essential for trapping moisture and keeping soil from eroding. Their deep root systems preserve water tables and help with percolation and habitat. But settlers there employed deep-plowing and dryland farming methods that lent themselves to wind erosion, which was exacerbated by tremendous droughts in 1934, 1936, and from 1939 to 1940. As the plains turned to desert, the wind came along and swept eroded, dead soil up into the air as dust, blotting out the daylight and causing respiratory distress for thousands. Many families plunged into poverty and were forced to leave their family farms—only to discover that the Great Depression made economic advancement unlikely no matter where one fled to.

Arthur Cofod Jr. // Wikimedia Commons

1937: The Hindenburg explosion changes air travel

Airships like the Hindenburg were seen in the 1920s and 1930s as the future of air travel. That changed in 1937 when the Hindenburg exploded above Lakehurst, New Jersey. The dirigible was circling the airport there while waiting out the rain that had moved in. Floating among the rain clouds created a negative charge on the airship’s cotton canvas skin. No sooner were the Hindenburg’s lines dropped for docking than they created a ground for the electrical charge and metal frame of the airship, producing a spark that connected with leaking hydrogen. The Hindenburg began burning 200 feet over the airfield, falling to the ground in less than 40 seconds.

Puttnam and Malindine // Wikimedia Commons

1940: A storm cloud saves Allied soldiers trapped near Dunkirk

With Axis forces closing in on them in the early part of World War II, around 330,000 Allied soldiers were stuck on English Channel beaches near Dunkirk. With the German Air Force nearby, the much smaller Royal Air Force had no hope of pulling off a successful rescue mission. Then, a storm cloud blew in and sent heavy rain into the area, grounding the German planes that had already killed many Allied soldiers along the beaches.

The English Channel—regularly subjected to strong winds—next turned unusually calm and was cloaked in a dense mist, allowing the Allied members of the military and even nearby residents to chart the Channel and rescue soldiers between May 26 and June 4, 1940, in what was called “Operation Dynamo.”

Wilhelm Gierse // Wikimedia Commons

1941: Winter breaks apart Hitler’s two-front war

Hitler sent 3 million of his troops to the Soviet Union on June 22, 1941, in a surprise attack designed to take the region over in fewer than three months. But soldiers were still there when Russia’s frigid winter set in, and the troops were desperately low on winter gear like gloves, hats, long johns, and coats. Clothing rationing over the two years prior meant there was little to send in from Germany, and almost nothing could be stolen from the invaded Russians and Poles.

German troops succumbed to the weather, losing eyelids, limbs, noses, and even hair to the heavy frosts. The forces were severely weakened. The troops precariously arrived in Moscow in early December, only to be stopped by Soviet counterattacks and forced to embark on a desperately slow retreat. Ultimately the Germans were able to restore some of their might; operations ceased by 1942. The takeover, coined Barbarossa, had ultimately not succeeded, and Nazi Germany’s two-front war was beginning to lose steam.

Robert F. Sargent // Wikimedia Commons

1944: D-Day

In order to successfully pull off the initially planned invasion of France on June 5, 1944, General Dwight D. Eisenhower needed certain very important weather events to happen at the same time: low tide so soldiers could see and dismantle mines placed in the water by the Germans, a full moon without cloud cover to help with visibilities, and little wind.

Eisenhower got no such weather report from weather forecasts, and all but one of his meteorologist teams thought June 5 would not work. The general considered postponing the invasion by two weeks to the next proper alignment of the moon and tides, but one meteorologist—Group Capt. James Stagg—advised postponing things by just one day. Eisenhower listened, famously saying “OK, we’ll go,” and the invasion of Normandy happened on June 6. Allies had also cracked the Enigma code of the Germans, allowing them to discover the Axis forces anticipated bad weather June 6 and therefore did not expect an attack from the Allies. The D-Day invasion stands as a major turning point in World War II and a direct line to the liberation of France and the defeat of Germany by the following year.

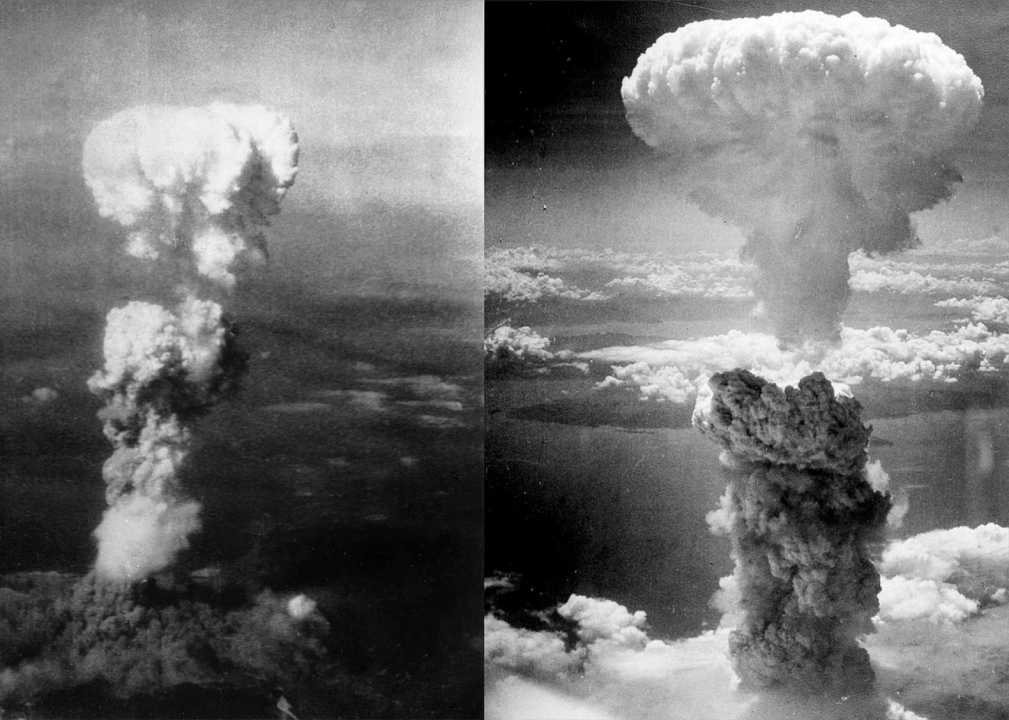

George Robert Caron and Charles Levy // Wikimedia Commons

1945: Kokura gets spared—twice

Sunshine over Hiroshima on Aug. 6, 1945, meant the skies were clear for the first nuclear weapon ever to be used in war to be dropped from overhead, killing 146,000 people over the course of the next four months and sparing Hiroshima’s back-up target of Kokura.

Kokura dodged tragedy again just days later, when the second nuclear weapon was already loaded in a B-29 destined for the town but not dropped because of overcast skies, drifting smoke, and obscured visibility from coal tar being intentionally burned by the Yahata Steel Works. Low on fuel after several passes over the town, the bomb ended up being dropped over the backup city of Nagasaki on Aug. 9., where upwards of 80,000 people were killed.

UCLA Library // Wikimedia Commons

1948: Air inversion in Donora, Pennsylvania

The Clean Air Act—among the most comprehensive air-quality bills throughout the world—was passed in 1963, following the 1955 signing of the Air Pollution Control Act. But the beginnings of such legislation came from Donora, Pennsylvania, where an “air inversion” in 1948 goes down in history as one of the worst air pollution disasters in the United States. It caused breathing issues for more than 40% of the 14,000-person population in the mill town.

Donora was home to U.S. Steel’s Donora Zinc Works and American Steel & Wire plant, which together released high emissions of sulfur dioxide, fluorine, nitrogen dioxide, hydrogen fluoride, and other toxic gases into the air. On Oct. 27, 1948, that air got trapped by an inversion of warmer air containing the airborne toxins in cold air across the valley town. The fog quickly became a yellow smog that stayed heavy in the air for five days until heavy rains came and broke the spell.

All told, 20 Donorans died by November—and another 50 died from respiratory illnesses a month later. The deaths directly resulted in new pushes for clean air laws in Pennsylvania and throughout the United States.

Victor Hugo King // Wikimedia Commons

1963: Sunny skies clear the way for JFK’s assassination

A bad storm in 1960 is believed to have kept Republicans out of voting booths on election day and helped usher John F. Kennedy into the White House. Three years later, an opposite weather event may have once again sealed Kennedy’s fate.

The young president notoriously hated traveling in vehicles with “bubble tops,” preferring closer interactions with his constituents. Light rain fell on the morning of Nov. 22, 1963, when Kennedy was scheduled to be in a motorcade through Dallas, so the plexiglass bubble top had been placed on the convertible.

When the sun came out, the plexiglass was removed. To this day, there is speculation about who is ultimately responsible for Kennedy’s assassination. However, it is all but certain that no bullet would have reached the president if the bubble top had remained on the convertible.

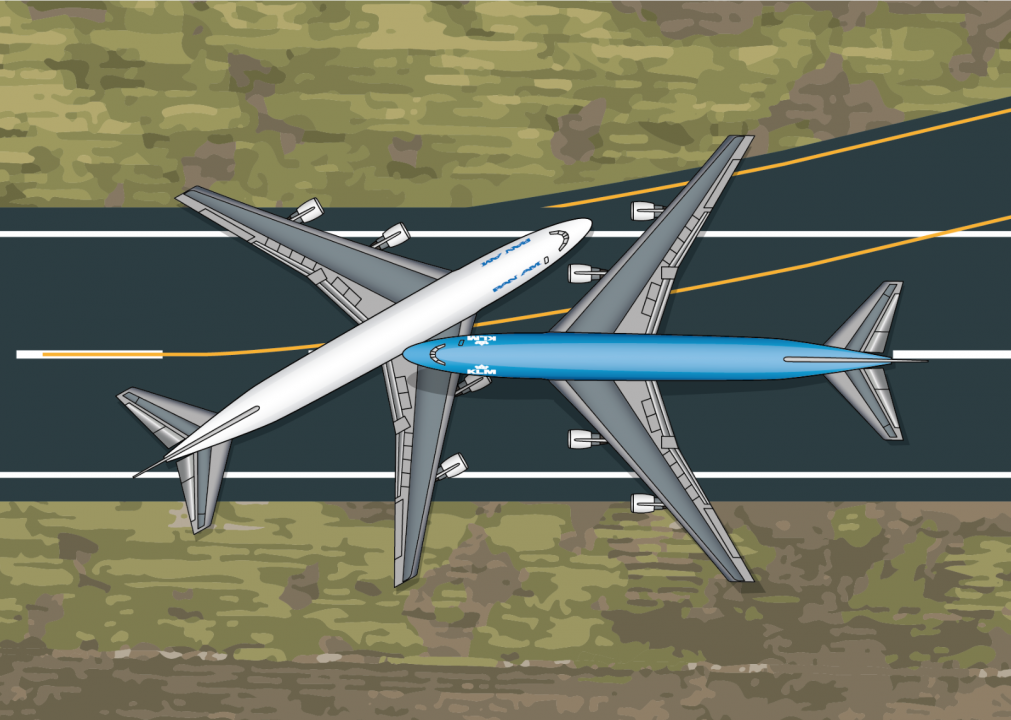

SafetyCard // Wikimedia Commons

1977: Tenerife Air Disaster

Heavy fog on March 27, 1977, and the runway tragedy it caused led to mandated Crew Resource Management training following what remains the world’s deadliest on-ground aircraft crashes. Boeing 747s KLM Flight 4805 and Pan Am Flight 1736 collided on the runway of present-day Tenerife North Airport on Spain’s island of Tenerife due to highly reduced visibility and poor communication, killing 583 people.

Unknown // Wikimedia Commons

1980: Iranian ‘haboob’ thwarts hostage rescue, secures Reagan election

President Jimmy Carter ordered Operation Eagle Claw on April 24, 1980, to rescue 52 hostages from the U.S. embassy in Tehran and effectively end the Iran hostage crisis. During the operation, three of eight helicopters malfunctioned and six others got caught in a violent sand and dust storm (called a haboob), which contributed to pilot fatigue, mass confusion, and a dramatic slowing of the helicopters. The mission was called off. During the retreat, another helicopter smashed into a transport plane, killing eight soldiers. It would be another 270 days before the hostages were freed.

Carter attributed his loss to Ronald Reagan in the 1980 U.S. presidential election to the failure of Operation Eagle Claw.

NASA // Wikimedia Commons

1986: The Challenger disaster

Lousy weather and some technical issues on the morning of Jan. 22, 1986, delayed the takeoff of space shuttle Challenger by six days. On the morning of Jan. 28—just 73 seconds after takeoff—the shuttle broke apart and exploded, killing all seven of its crew members.

Upon review of the video footage from the disaster, technicians and engineers discovered hot gas spilling from a broken rubber O-ring meant to seal the Challenger’s booster rocket joint. The O-ring’s malfunction was directly due to the record-low temperature on that day of just 26 degrees Fahrenheit; documentation shows a recommendation against launching a shuttle in temperatures below 53 degrees Fahrenheit.

On board were astronauts Gregory Jarvis, Ronald McNair, Ellison Onizuka, Judith Resnik, Francis Scobee, Michael J. Smith, and teacher Christa McAuliffe, who would have been the first civilian to travel to space.