Will the chip shortage end in 2023?

![]()

Canva

Will the chip shortage end in 2023?

A board of semiconductor chips.

A global shortage of semiconductors has had a major impact on the automotive supply chain, forcing automakers around the world to cut production over the last two years due to the lack of these crucial parts. As COVID-era regulations begin to relax, some – but not all – industry insiders speculate that the chip shortage may come to an end in 2023. To understand the forecast for chip shortages in the U.S., Automoblog took a closer look at industry forecasting and expert reports to see if the auto chip shortage is expected to improve—and by how much.

Automotive manufacturers are still dealing with the effects of the microchip shortage that began in 2020. Sam Fiorini, vice president of global vehicle forecasting at AutoForecast Solutions, told reporters that he believes the industry will see 2-3 million units cut from production in 2023.

This figure highlights the continued production difficulties that manufacturers face. However, if Fiorini’s estimate holds true, it would mark a significant improvement for the industry.

More than 10.5 million vehicles were cut from production in 2021, according to Auto News. In 2022, automakers around the world cut an estimated 4.3 million cars from their production schedules. Losing 2 to 3 million units would still be a hardship for manufacturers, but it would indicate that supply chain issues are beginning to ease.

![]()

Automoblog

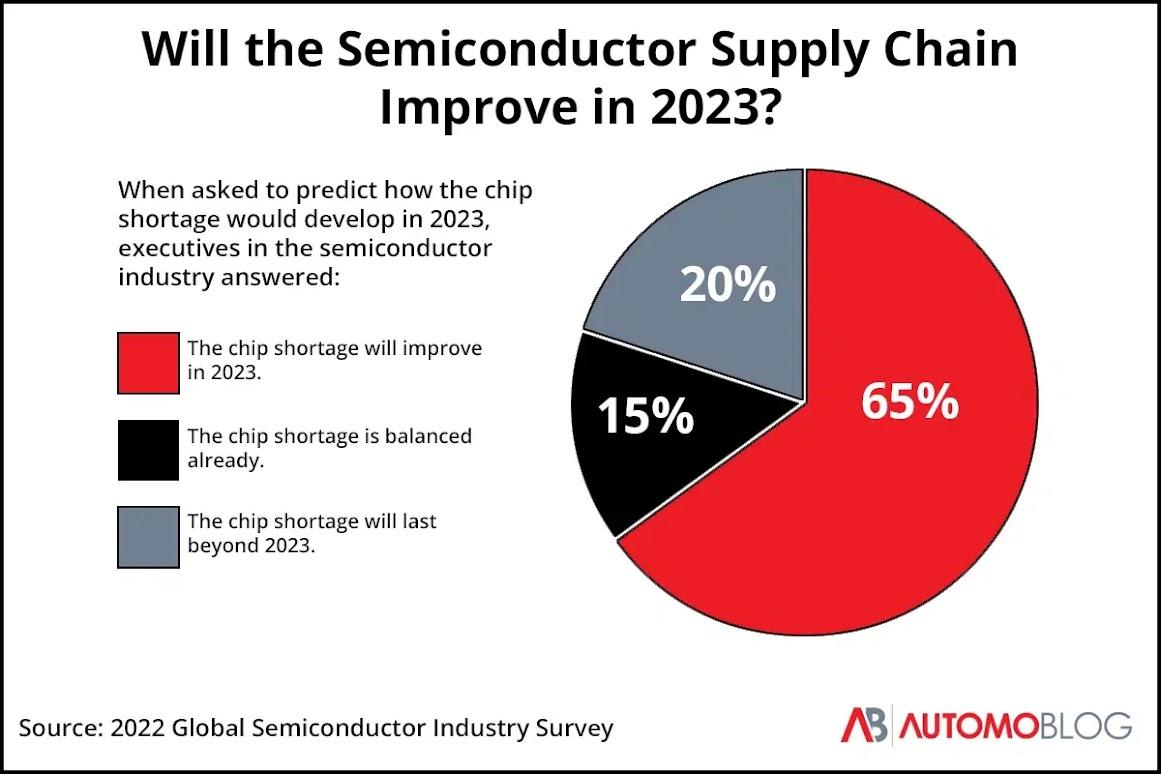

Semiconductor industry executives are cautiously optimistic about 2023

A pie chart showing how survey respondents answered the question, will the semiconductor supply chain improve in 2023?

Many key players in the semiconductor industry are feeling positive about the direction of the chip shortage in 2023, according to a recent poll. Multinational accounting firm KPMG and the Global Semiconductor Alliance (GSA) conducted the 18th annual global semiconductor survey in Q4 of 2022.

The poll asked 151 semiconductor executives about their outlook for 2023 and into the future. Of those executives, more than half represent companies posting more than 1 billion USD in annual revenue.

Based on the results, the Semiconductor Industry Confidence Index for 2023 currently stands at 56 out of 100. This score indicates that a small majority of respondents have a more positive outlook for 2023 than negative.

The survey asked semiconductor executives when they think the chip shortage will subside. Of those, 65% said that they believe the shortage would end in 2023 while 20% said they believe that it would extend into 2024 or later. Around 15% of respondents said they believe chip supply and demand are currently balanced.

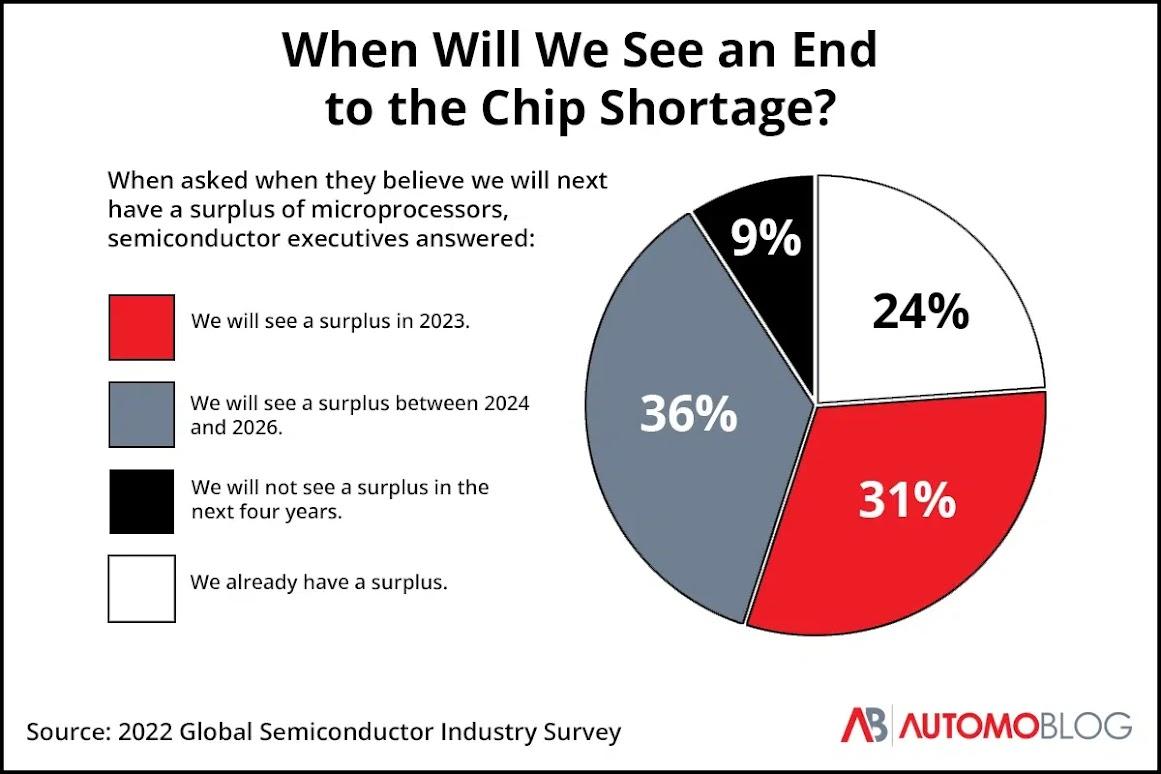

Executives were also asked when they believe there will be a net excess of semiconductors. Around 31% said they believe there will be a surplus by the end of 2023, while 24% stated that they believe there is already a semiconductor surplus. That means that over half of respondents think that we will see a surplus in this calendar year, if we haven’t already.

However, 36% believe that the next surplus won’t happen until between 2024 and 2026, and 9% said they believe the industry won’t see a surplus at any time in the next four years.

Automoblog

For automakers, the 2023 outlook is mixed

A pie chart showing how survey respondents answered the question, when will we see an end to the chip shortage?

The effects of the automotive chip shortage do not appear to have been evenly distributed between manufacturers. Some companies, such as BMW, Mercedes, and Volvo, reported no significant chip supply issues early in the second half of 2022. Others like Nissan, Hyundai, and Volkswagen said that semiconductor issues were improving at that time.

But many of the world’s largest manufacturers are still facing significant difficulties related to the microprocessor shortage heading into 2023. Honda, General Motors, Ford, and Toyota all reported significant chip supply issues in the second half of 2022. General Motors suggested that those issues would continue into this year.

In an interview with Automoblog, Jennifer Strawn explained why there doesn’t seem to be a consensus on when the shortage will end. Strawn currently serves as Executive Vice President of Global Solutions and Sourcing at Rand Technology, a leading global sourcing and supply chain solutions company.

“While the chip shortage is improving, there is still uncertainty about semiconductor supply availability,” she says. “Increased buying during the peak of the electronic component constraints and decreased demand for consumer electronics at the end of 2022 left many [original equipment manufacturers] OEMs and contract manufacturers with an imbalance of inventory.”

Strawn observes that this has resulted in some companies being more affected by the shortage than others, hence the varying outlooks.

“In some instances, they have a surplus,” she says. “However, many are still missing the ‘golden screws’ – the parts needed to complete production.”

Canva

Car manufacturers are making adjustments in response to the chip shortage

An assembly line in an automotive manufacturing plant.

The number of vehicles cut entirely from production schedules doesn’t tell the entire story, either. Some automakers have been able to limit the number of vehicles cut from production by rationing the chips they use, removing some features that rely on microprocessors.

Mercedes-Benz, for example, removed features like premium audio and wireless phone charging from several vehicles. General Motors got rid of the assisted-driving feature Super Cruise from its Cadillac Escalade, along with vented and heated seats on a few of its trucks and SUVs. BMW removed parking assist and even touchscreen functions from several models. The company also pulled the semi-autonomous driving feature from the X3, its most popular model.

In many cases, these companies offered reimbursements for the lack of these features. Drivers who bought these cars may also be able to retrofit some of the features when the chip shortage diminishes.

Chip shortage: factors at play

Predicting the end of the microprocessor shortage is difficult because of the complex and global nature of the supply chain. There are a number of variables that affect manufacturing and distribution throughout the world.

Businesses in the semiconductor industry have responded to the shortage by investing in increasing their manufacturing capacity. In Germany, Bosch invested more than $1 billion in 2022 to help ramp up production. The company also has plans to spend another $3 billion towards expanding its production capacity in the near future.

The first semiconductor fabrication plant in the U.S. opened its doors in Marcy, New York in August, 2022. Built by North Carolina-based Wolfspeed, the $1 billion factory produces 200 millimeter silicon carbide wafers for domestic and international manufacturers.

This factory is set to be just one of many to come following the passing of the Creating Helpful Incentives to Produce Semiconductors (CHIPS) for America Act in August, 2022. The new law could provide as much as $52 billion towards funding new chip manufacturing projects.

According to Semiconductors.org, companies have announced more than $200 billion in investment in the build-up to and wake of the passing of the CHIPS Act. These investments span more than 40 projects across 16 states.

Investments like these around the world should result in a noticeable increase in production capacity in 2023. That increased capacity could play a vital role in alleviating chip supply shortages.

However, Strawn warns that solving supply chain issues is more complicated than simply making more semiconductors.

“The issues don’t just concern high-level infrastructure,” she says. “The sub-infrastructure must also be ready to tackle future demands. An investment into new wafer foundries, substrates, OSAT [outsourced semiconductor assembly and test] capability and producing and sourcing key raw materials – including cobalt, palladium, copper, neon gas, and others – is required to support the build-out, and meet next-gen hardware needs.”

Canva

Semiconductor suppliers are playing catch-up

Electric vehicles charging at a charging station.

In 2023, semiconductor manufacturers aren’t just trying to meet current demand. They’re also trying to fill backorders resulting from the last several years of issues.

Even with increased investment and capacity, doing both simultaneously presents a serious challenge. In other words, one of the main obstacles to the recovery of the supply chain shortage is the shortage itself.

“I expect some companies will spend a decent portion of the year trying to absorb or sell surplus supply while looking to obtain vital parts to complete the manufacturing process,” says Strawn.

Changes in demand for semiconductors

The chip shortage presented at the same time as demand for microprocessors began rapidly increasing. Despite the recent setbacks, the long-term outlook for the semiconductor industry remains strong in part due to automotive manufacturing needs. An 2022 analysis from McKinsey estimated that the auto industry accounts for roughly 20% of microprocessor demand.

Automakers are using more semiconductors in all vehicles, as these feature an increasing number of computer-controlled components. Gina Raimondo, the U.S. Secretary of Commerce, said in 2022 that the average car uses more than 1,000 microprocessors.

However, demand for semiconductors has been supercharged by the increase in electric vehicles (EVs) hitting the market. Raimondo said that the average EV uses twice as many chips as gasoline-powered vehicles. As EVs take up an increasing market share, demand for the microprocessors that power them will continue to grow exponentially.

Canva

Geopolitical factors

Aerial view of a shipping container port in Shenzhen, China.

Some of the most impactful factors in the supply chain picture are more political than industrial. The global nature of the semiconductor industry means that the supply chain is vulnerable to government policies and geopolitical developments.

End of COVID lockdowns in China

Delays in manufacturing and logistics difficulties in China due to COVID lockdowns are one of the primary drivers of the chip shortage. Under the country’s zero-COVID policy, factories, ports, and even entire cities were frequently forced to cease activity to prevent the spread of the disease since 2020.

However, officials in Beijing announced the end of the zero-COVID policy in late December 2022. The loosening of regulations could help to increase production and improve shipping logistics, resulting in greater inventory and a more reliable supply chain.

Strawn says this could be a significant step in returning stability to the supply chain.

“There is no doubt China’s rigid COVID policy put a lot of strain on many companies,” she says. “With the easing of restrictions, it will help alleviate some transportation issues and shutdowns, which will help get people back to work and ultimately improve the supply chain.”

Growing trade tensions between the US and China

Trade issues between China and the U.S. – the world’s largest trading partners – are nothing new. But tensions over microprocessor chips have begun to heat up in recent months.

In October 2022, the U.S. announced broad export restrictions that make it more difficult for Chinese entities to obtain advanced semiconductor technology. Some of the new measures include requiring a license to export chips that use American tools or software and banning sales to certain companies. The new rules also forbid green card holders to work for some Chinese semiconductor companies.

The U.S. maintains that the policies were designed to limit China’s access to “sensitive technologies with military applications.” But the measures could also impact China’s ability to develop advanced semiconductors and limit the country’s ability to contribute to the supply chain.

Chinese officials have responded by filing a complaint with the World Trade Organization (WTO) on December 15, 2022. The complaint alleges that the U.S. regulations have put “the stability of the global industrial supply chains” in jeopardy.

The U.S. had 60 days – until February 13, 2023 – to resolve the issues outlined in the complaint. Chinese officials could now request a WTO panel to review the matter, as there has yet to be any further movement on the issue at the time of press. It is not uncommon for WTO disputes to take years to resolve.

The ongoing Russian invasion of Ukraine

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022 has had a significant impact on the supply chain. Before the invasion, Ukraine was one of the largest suppliers of several raw materials used in semiconductor manufacturing, such as neon gas. Ongoing conflict has limited the country’s ability to capture, process, and export these materials.

An end to the invasion in 2023 could open Ukraine up again and remove a major bottleneck in the microprocessor manufacturing supply chain. But a continued invasion would mean manufacturers will need to find other sources for raw materials and sustained disruption.

![]()

Canva

When will the chip shortage end?

A silicon semiconductor chip being wirebonded.

The most optimistic take is that the semiconductor supply chain could return to “normal” by the end of 2023. Others think that the shortage could continue well into 2024.

But with demand for chips shifting and producers around the world ramping up auto production, it’s worth asking what the end to the shortage looks like. All of the shifts over the past two-plus years in the auto industry means that a fully-functioning supply chain looks different in 2023 than it did before the shortage began in 2020.

Strawn says that those seeking signs that the chip shortage is coming to an end should look for shorter and more consistent manufacturing lead times.

“Indicators of improvement would be consistent and ongoing deliveries from factories,” she says. “Lead times would also improve significantly.”

The phrase “new normal” has long past worn out its welcome, yet it pertains here as well. Perhaps a better question is not “when will the chip shortage end?” but “when will the next evolution of the semiconductor supply chain begin?”

This story originally appeared on Automoblog and has been independently reviewed to meet journalistic standards.