20 influential Indigenous Americans you might not know about

Etienne Montes/Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images

20 influential Indigenous Americans you might not know about

Sacheen Littlefeather in 1973

Most Americans can count on one hand the Indigenous Americans who they know contributed to the colonial history of this land—from Sacagawea and Geronimo to Pocahontas and Sitting Bull. However, the reality is the one-sided nature of American history taught to children in the U.S. has minimized the contributions of Indigenous people, making for a challenging journey to truth and reconciliation with the native people of this land.

With the discoveries of a burial site for Indigenous children in Albuquerque in September 2021 and the unmarked graves of children in Canada in the summer of 2021, the world finally began reckoning with the brutal realities of the boarding school system and the insidious legacy of colonization—injustices that Indigenous activists and concerned communities have been speaking up about for years.

Speaking as an expert on a panel about Indigenous boarding schools, Dena Ned, a member of the Chickasaw Nation of Oklahoma, stressed the importance of remembering and learning our history. By doing so, Ned explained, we can understand why it’s important for policies, systems, and institutions to recognize and respond to certain members of the community.

That’s starting to happen more and more. In August, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences formally apologized to Native American activist Sacheen Littlefeather for what she endured when Marlon Brando famously had her decline his 1973 Best Actor Oscar due to the mistreatment of Indigenous people in Hollywood.

By learning about the backgrounds, contributions, and sacrifices of Indigenous leaders, you can take action to break down the systems of oppression that threaten the rights of Indigenous peoples in the U.S. and around the world.

Backed by news articles and historical sources, Stacker compiled a list of 20 influential Indigenous Americans you might not know about, including Littlefeather who died in Oct. 2022. Read on to find out about these unsung Indigenous heroes and revolutionaries from across North America who resisted oppression, broke down barriers, and changed the course of history.

You may also like: Biggest Native American tribes in the U.S. today

![]()

Kean Collection // Getty Images

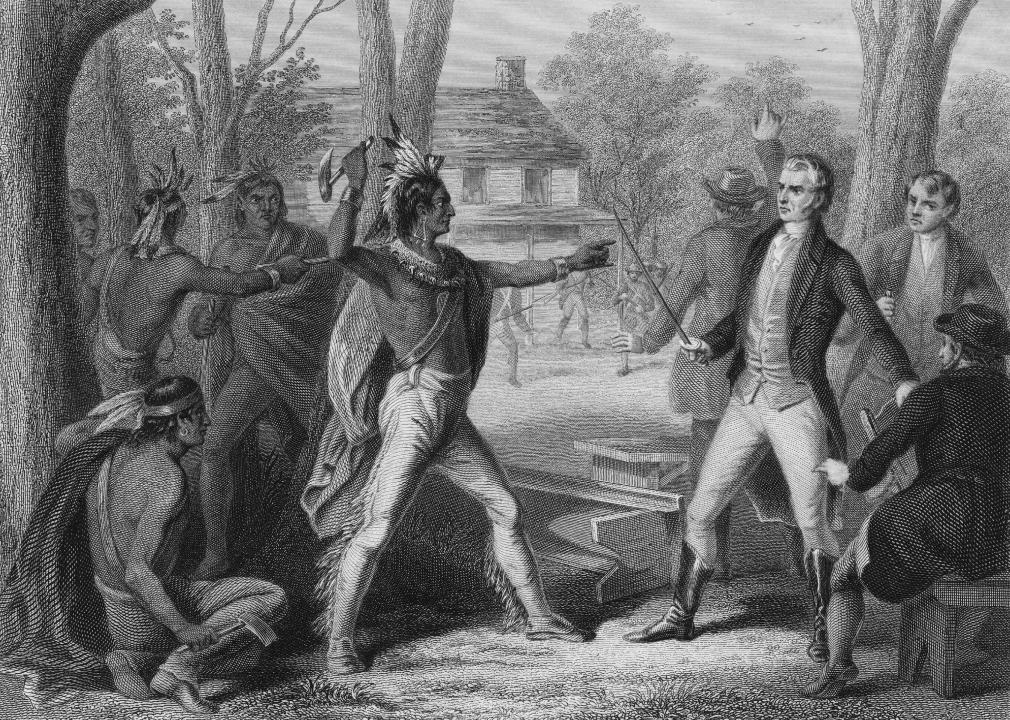

Tecumseh

Wedged between the American expansionists and the British invaders, Tecumseh was a Shawnee leader who attempted to carve out a sovereign Indigenous state in the Midwest. Tecumseh and his spiritually enlightened brother, Tenskwatawa, were descended from a long line of Indigenous leaders who fought for the land against the intruders. While Tecumseh’s mission failed, and he died in battle in 1813, his efforts exposed the duplicitous underbelly of the foundation of America. His impact in the Midwest contributed to The American Indian Movement, which was started in Minneapolis in the 1960s and continues its work to this day.

Bettmann // Getty Images

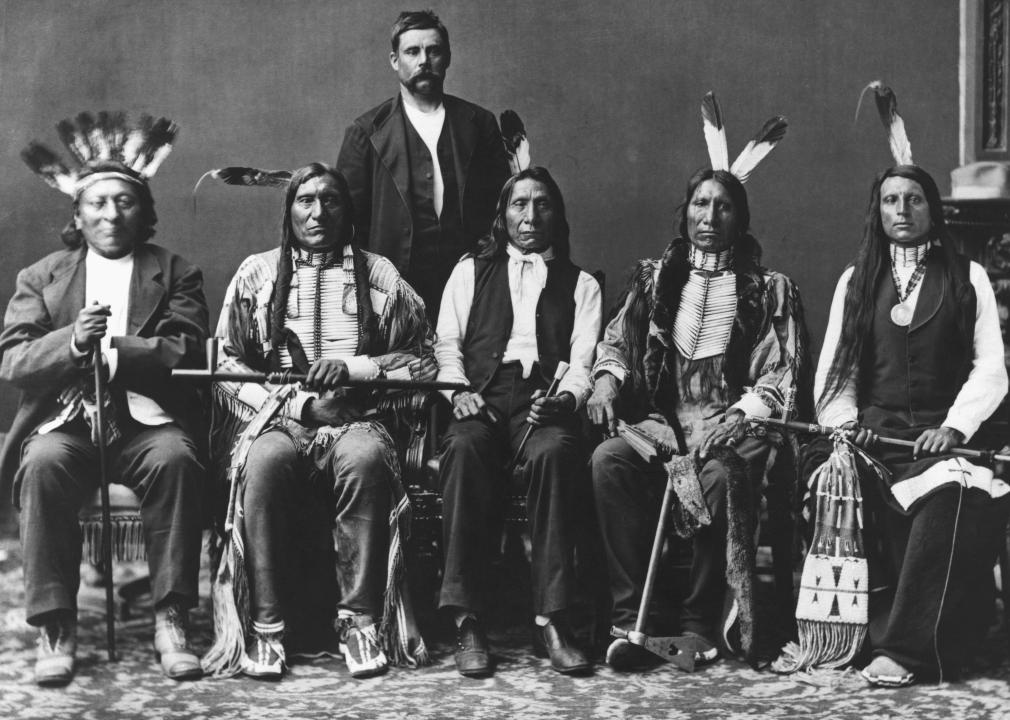

Red Cloud

Oglala Sioux chief Red Cloud was among a group of Indigenous leaders who confronted the white settlers who had discovered gold in Montana during the 1860s. The settlers had attempted to construct a road lined with protective forts to facilitate the mining of this gold. However, following a two-year battle, Red Cloud and his army were able to halt the construction of this road and caused the U.S. to abandon its forts. Red Cloud then signed a treaty securing land in Wyoming, Montana, and South Dakota for his people. A warrior turned diplomat, Red Cloud was committed to nonviolent advocacy. Later in life, after settling in the Pine Ridge Reservation, Red Cloud campaigned for Indigenous land and civil rights in Washington.

Henry Rocher // Wikimedia Commons

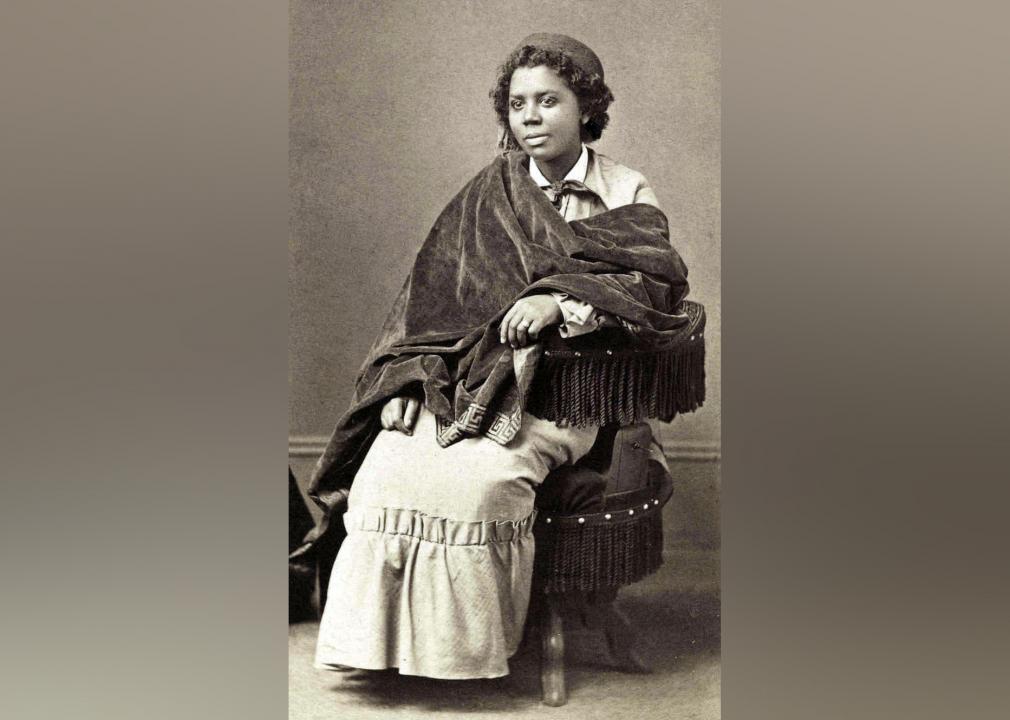

Edmonia Lewis

One of the first Black professional sculptors, Edmonia Lewis broke down both racial and gender barriers with her works of art standing tall in the Smithsonian and the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Born in 1844 to a Haitian father and Ojibwe mother, Lewis has a shared African and Indigenous American heritage, though she was orphaned by the age of 7. Her most famous work of art is the marble “The Death of Cleopatra,” which was carved in 1876 and acquired by the Smithsonian in the 1990s. Lewis spent time sculpting in Europe, and many of her sculptures speak to the Black experience throughout history.

The National Library of Medicine // Wikimedia Commons

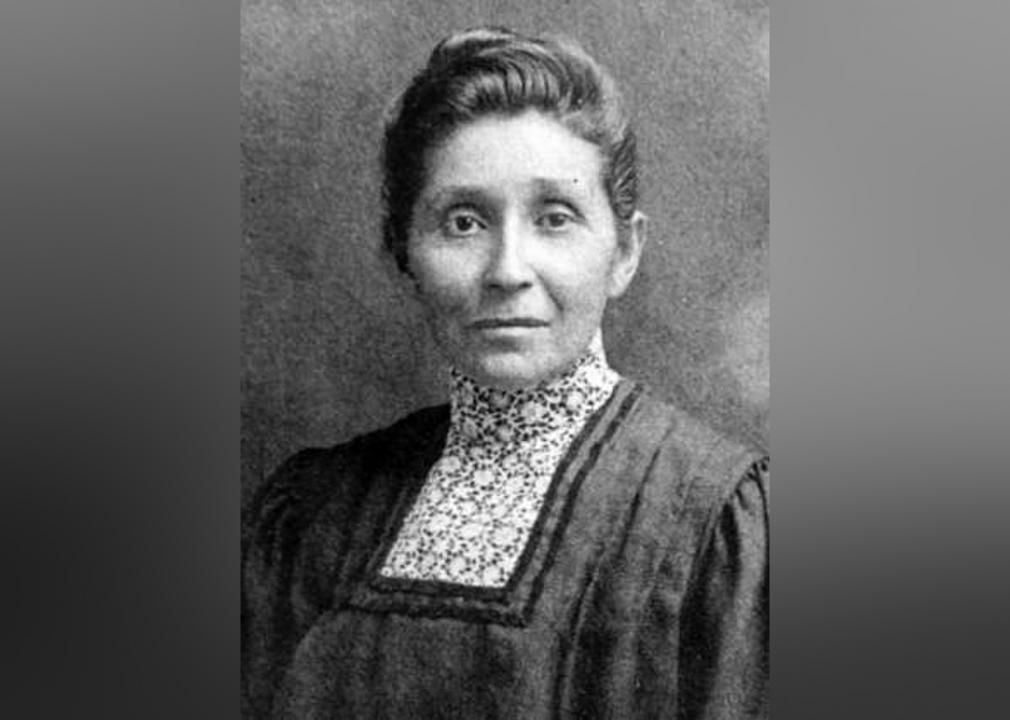

Susan La Flesche Picotte

Born on Nebraska’s Omaha reservation in 1865, Susan La Flesche Picotte was young when she first saw a sick Indigenous community member suffer and die while waiting for a white doctor. By pursuing a Euro-American education while honoring the customs of her people, La Flesche Picotte battled backlash and became the first Indigenous person to earn a medical degree. She defied the odds again in 1913 when she opened the Omaha reservation’s first hospital. La Flesche Picotte died in 1915, and she was commemorated on her deathbed for bridging the gap between her Indigenous roots and her Euro-American medical education.

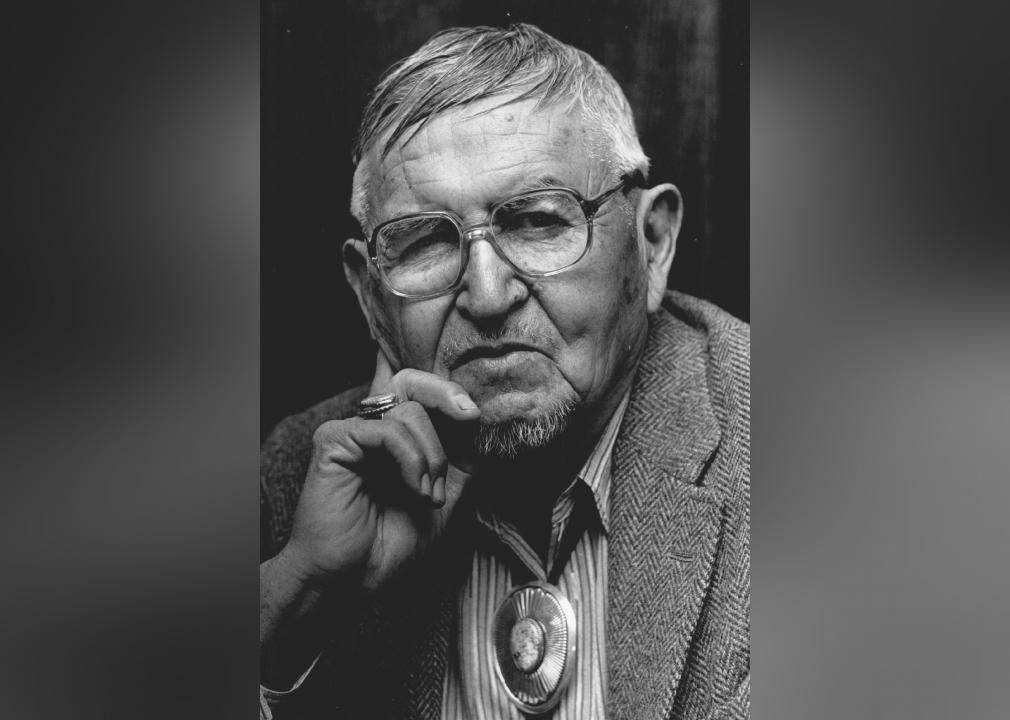

Denver Post // Getty Images

Allan Houser

Indigenous sculptor Allan Houser is considered to be among the most influential artists of the 20th century. His parents, members of the Chiricahua Apache tribe, were held as war prisoners for 20 years, and his family tree includes legendary Apache leader Geronimo, who was a first cousin to Houser’s father. Houser’s career began in 1939, when he was commissioned by the U.S. government to paint murals. He was one of the first Indigenous artists to receive the National Medal of Arts in 1992, and his statue, “Swift Messenger,” sits in President Biden’s Oval Office today.

You may also like: LGBTQ+ history before Stonewall

Michael Ochs Archives // Getty Images

Charlie Parker

One of the most prolific jazz musicians of our time, Charlie “Yardbird” Parker was a renowned saxophonist whose bebop style left a lasting effect on American culture. Born to a Black father and an Indigenous mother, the Kansas City native would go on to collaborate with the likes of Miles Davis and Dizzy Gillespie. The Grammy-award winner’s influence on the jazz art form was undeniable, and in 2021, the American Jazz Museum committed to celebrating his legacy by raising funds for youth activities and enhanced programming. Parker’s iconic works of art will be digitized and preserved by the museum for future generations.

Bettmann // Getty Images

Maria Tallchief

Maria Tallchief moved to New York to achieve her dream of becoming a dancer at just 17 years old. However, many of the companies she approached turned her away because of her Osage Nation heritage. Her drive and determination against all odds, even refusing to change her last name, led her to become one of America’s most revered ballerinas. Tallchief was the first American to perform at the Paris Opera Ballet, and she and her sister Marjorie went on to found the Chicago City Ballet.

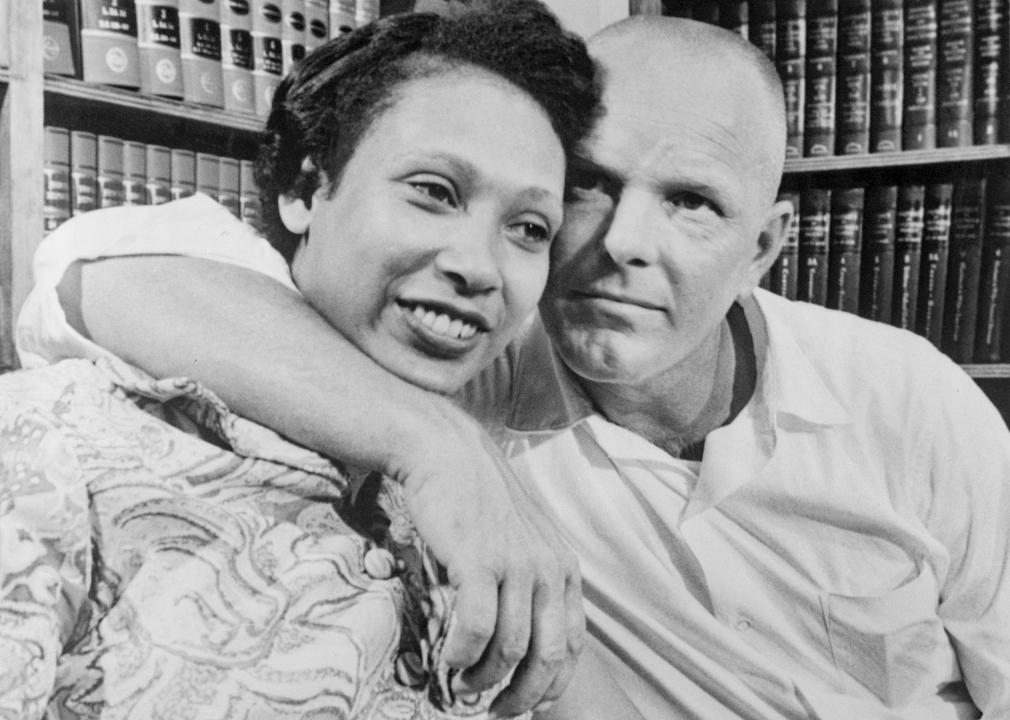

Bettmann // Getty Images

Mildred Loving

Many Americans will have heard of Mildred Loving, as she and her husband (and co-plaintiff) Richard battled the ban against interracial marriage in the super-charged case of Loving v. Virginia. What many Americans may not know is that Mildred Loving was of Black and Indigenous descent. The Lovings took their case to the Supreme Court in 1967 and won, legalizing interracial marriage across the nation. In order to exclusively focus on the white–Black binary that was dominating American discourse around race, coverage of the Loving v. Virginia case—as well as the 2016 film “Loving”—left out Mildred Loving’s multiracial heritage.

Mark Wilson // Getty Images

Ben Nighthorse Campbell

The National Native American Veterans Memorial opened its doors to the public on Veterans Day in 2020. This museum honors the contributions of the Indigenous community and would not have been erected without the support of former Colorado senator Ben Nighthorse Campbell. When Campbell was elected in 1992, he was the first Indigenous American to serve in the Senate in over 60 years and the only Indigenous American in Congress. Beside being a former congressman and a member of the Northern Cheyenne tribe, Campbell is a Korean War vet, former Olympian, rancher, and jewelry designer.

Peter Turnley // Getty Images

Wilma Mankiller

One of Time magazine’s 100 Women of the Year in 2020, Wilma Mankiller was the first woman to be appointed Principal Chief of Cherokee Nation. Mankiller faced discrimination and racism growing up, which fueled her commitment to feminism and self-governance for Indigenous people. The Cherokee community thrived under her two terms as Principal Chief. She passed away in 2010, leaving a legacy of prosperity, pride, and hope.

You may also like: How well do you remember 1969?

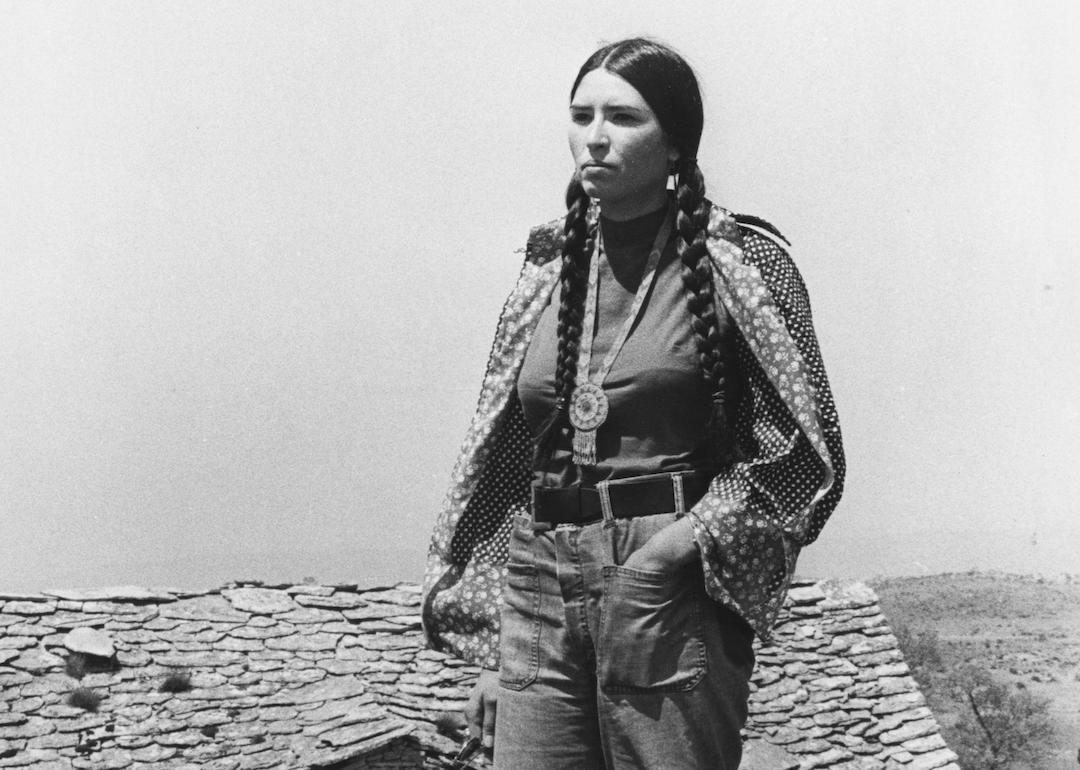

Bettmann // Getty Images

Sacheen Littlefeather

Sacheen Littlefeather made history at the 1973 Academy Awards when she accepted the award for Best Actor on behalf of Marlon Brando. Littlefeather’s speech, which protested the film industry’s treatment of Indigenous people, may have caught the audience off guard, but she is proud to be the first Indigenous woman to have used the Academy Awards as a platform. In August, when the Academy apologized to Littlefeather nearly 50 years later, she told The Hollywood Reporter, “I was stunned. I never thought I’d live to see the day I would be hearing this, experiencing this.” She added, “As my friends in the Native community said, it’s long overdue.”

Born to a father of Apache and Yaqui heritage, Littlefeather dedicated herself to advocating for the rights of Indigenous people across film, TV, and sports. As an elder, she mentored members of her community, sharing her knowledge with future generations. Just a few months after the Academy’s apology, Littlefeather died at 75 on Oct. 2, 2022. A cause of death was not announced, but she had been living with metastasized breast cancer after being diagnosed in 2018.

VALERIE MACON // Getty Images

Joy Harjo

America’s first Indigenous poet laureate, Joy Harjo wants her writing to reflect the humanity of her people. Her work is guided by the need for justice and the desire for respect experienced by the Indigenous community. Harjo lives in Tulsa, Oklahoma, and is a Muscogee (Creek) Nation member whose grandfather endured the tragedies of the Trail of Tears. Harjo was an artist and an activist growing up, and today, she elevates her people and honors the spirits of her ancestors with every word.

Public Domain // Wikimedia Commons

Charlene Teters

For many years, artist, educator, and activist Charlene Teters has been committed to removing Indigenous cultural appropriation in the state of Illinois. A member of the Spokane tribe and former Academic Dean of the Institute of American Indian Arts, Teters is a powerful and creative voice in the movement for change. Decades after she protested the University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign’s mascot, Chief Illiniwek, the school finally removed the mascot. The fight against appropriated mascots, however, is not over yet.

Ulf ANDERSEN // Getty Images

Louise Erdrich

The Pulitzer Prize–winning author of “The Night Watchman,” Louise Erdrich has written children’s books, novels, poetry, and a memoir. A member of the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa Indians, Erdrich lives in Minneapolis where she owns an independent bookstore. The award-winning author elevates the history and culture of her people, especially the Indigenous community in North Dakota, and is deeply connected to their fight for survival.

Gildir // Wikimedia Commons

John Herrington

When the STS-113 Endeavour launched from Kennedy Space Center in November 2002, it carried the first Indigenous American into space. John Herrington carried the Chickasaw Nation flag, a traditional flute, and a few other personal items with him. His journey has seen him as a naval officer, a NASA astronaut, and on the big screen, in the IMAX movie “Into America’s Wild.” With a passion for Indigenous oral storytelling and a love for science, Herrington travels the world to tell his stories from the stars. He wants to encourage more Indigenous youth to get into the STEM fields and reclaim their ancestral legacy of engineering, astronomy, and science.

You may also like: 25 terms you should know to understand the health care debate

Alex Wong // Getty Images

Deb Haaland

Deb Haaland made history in March 2021 when she was confirmed as U.S. Cabinet secretary. The first cabinet secretary of Indigenous American heritage, Haaland is at the forefront of conservation efforts and the fight against climate change, telling NPR that she believes tribal consultation is necessary when addressing environmental issues. Regarded as a “barrier-breaking public servant” by the Biden administration, Haaland is positioned to play a pivotal role in the movement toward a greener future.

Randy Risling // Getty Images

Kent Monkman

A creative visionary whose work has been commissioned by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Kent Monkman is a Swampy Cree artist born in Canada. His work centers on the effects of Christianity on Indigenous communities. With solo exhibits across Canada and group exhibits throughout North America, Monkman’s impactful art challenges conventional depictions of his people by white artists like Paul Kane.

Doug Gifford // Getty Images

Lila Downs

Lila Downs has always felt pulled between her cultures. The artist grew up in two worlds, Minnesota and Oaxaca, Mexico, and is also Indigenous Mixtec, making her a tricultural creative. Her multifaceted heritage shines through in her entertaining and inspiring music, and she uses her songs to tell stories of her people. Inspired by these stories, her song “Dark Eyes” is about the labor Indigenous communities often take on, which is often deemed “essential” yet overlooked.

Whitney Curtis // Getty Images

Sharice Davids

A member of the Ho-Chunk Nation of Wisconsin, Representative Sharice Davids was a professional athlete, business owner, lawyer, and nonprofit executive before she was elected to Congress in January 2019. As one of the two Indigenous American women serving in Congress, Davids is dedicated to reducing poverty, creating safe working conditions, and closing the pay gap for Indigenous women.

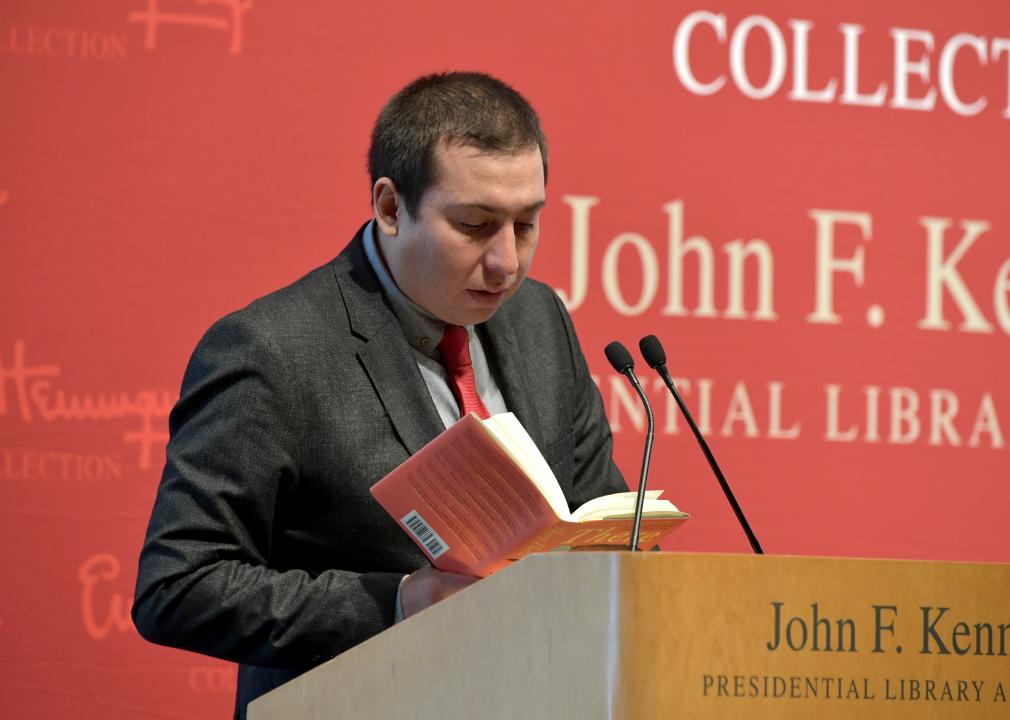

Paul Marotta // Getty Images

Tommy Orange

Author Tommy Orange is a member of the Cheyenne and Arapaho tribes, but he wasn’t surrounded by the Indigenous community in his hometown of Oakland, California. His debut novel, “There There,” won an award at the 2018 National Book Circle Awards. In sharing the Indigenous perspective in a contemporary way, Orange speaks about the relocation of his people to the cities and how assimilative culture has left many Indigenous communities feeling “voiceless” and underrepresented.

You may also like: 25 terms you should know to understand the gun control debate