The Vatican is investigating a miracle at a Connecticut church. Here's every Eucharistic miracle visualized.

Massimo Todaro // Shutterstock

The Vatican is investigating a miracle at a Connecticut church. Here’s every Eucharistic miracle visualized.

Communion rite during Catholic mass.

On March 5, during Sunday Mass at St. Thomas Church in Thomaston, Connecticut, a parishioner noticed that the wafers, or hosts, given during Communion—also called the Eucharist—multiplied themselves inside the ciborium just as they were about to run out. With no explanation available other than alleged divine intervention, the Vatican is now investigating whether it was a true Eucharistic miracle. If confirmed, which is unlikely now due to a lack of physical evidence, it would be the first miracle of any kind declared by the Catholic Church in the United States.

Believing in miracles is a prerequisite of Roman Catholicism. Church doctrine teaches that Jesus, the son of God, enters the world by immaculate conception, or virgin birth. He rises from the dead. And in between the bookends of his life, he performed many alleged miracles, including walking on water, turning water into wine, and feeding a crowd of 5,000 people with only two fish and five loaves of bread.

In Catholicism, miracles are perceptible events with no natural or scientific explanation. But not just any random, inexplicable phenomenon gets the holy seal of approval. These events typically involve healing, curing, or strengthening faith and are most often discussed in the context of canonization, as performing a miracle is a required criterion of sainthood.

Over time, verifying these events has become more rigorous and scientific. Miracles evolved from being supernatural signs of God, according to the church, to proof of God. Where science finds future progress and discovery in inexplicable events—things yet to be solved—the Catholic Church finds God. They are two sides of the same coin; which side is up depends on who is holding it.

The church has a long history of preempting the skeptics in order to strengthen their arguments for proof. In 1587 Pope Sixtus V established the position of advocatus diaboli. The primary function of this role was to find any and every reason to question a person’s candidacy for sainthood. This went beyond questioning the validity of miracles they performed to even include identifying selfish reasons for good deeds completed by the person in question. Today, we call people who present counterarguments like this a devil’s advocate—or, in Latin, advocatus diaboli.

To better understand the history of Eucharistic miracles specifically, Stacker visualized every Eucharistic miracle the Vatican has declared, charting their prominence over regions and time with help from a list compiled by miracolieucaristici.org. The events only include those in which some action occurred and exclude relics or feasts often grouped in with Eucharistic miracles.

![]()

Emma Rubin // Stacker

No Eucharistic miracles have been declared in the US

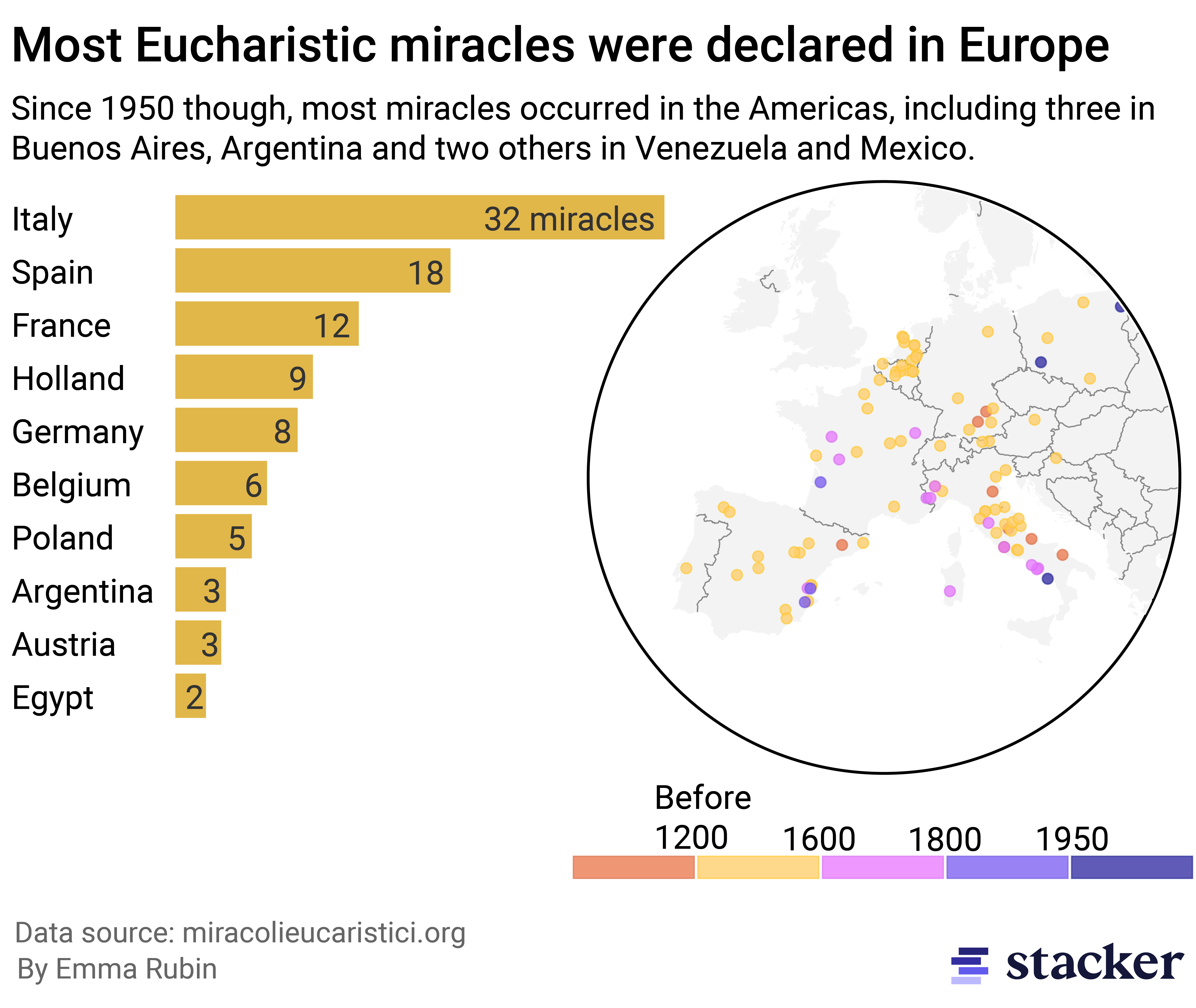

Bar chart and map showing Europe leads miracle counts, largely due a surge between the 13th and 17th century.

The geographic distribution of miracles largely reflects regions with the largest number of Catholics at the time. During the Middle Ages—spanning roughly 1,000 years between A.D. 500 and 1400—Catholicism was the only recognized religion in Europe.

During the 20th century, however, the global distribution of Catholics changed dramatically. Latin America and the Caribbean overtook Europe as the region with the largest share of Catholics. The Middle East and North Africa, Sub-Saharan Africa, Asia-Pacific, and North America also saw growth in the percentage of Catholics living in those regions.

Emma Rubin // Stacker

Eucharistic miracles peaked during the Late Middle Ages

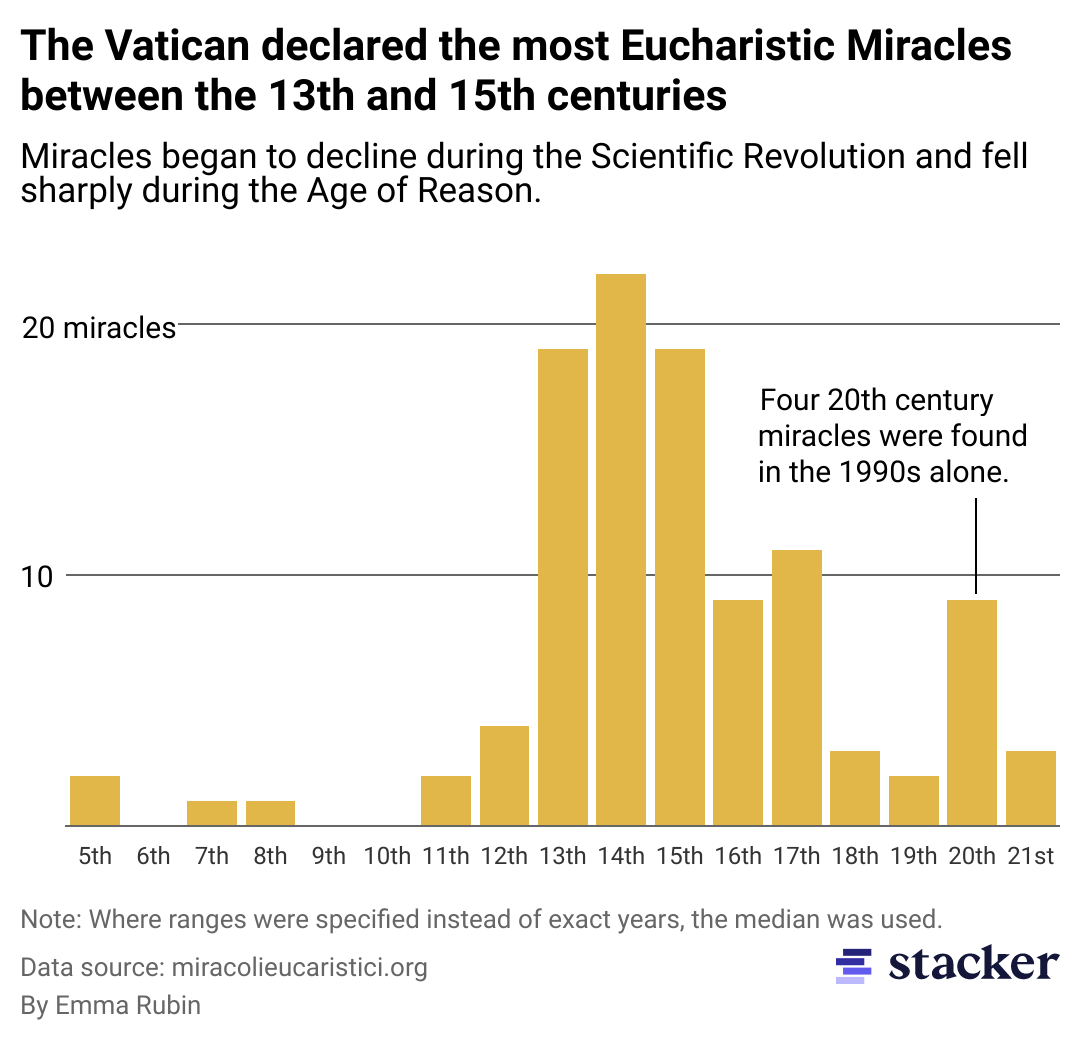

Column chart showing Eucharistic miracles peaked during the Late Middle Ages and became less prominent during the Scientific Revolution and later the Age of Reason. The 20th century saw nine miracles declared, an increase from the 18th and 19th centuries.

Medieval life—for peasants, nobles, and all classes in between—was heavily influenced by Christianity, perhaps more so than at any other point in history. Popes replaced kings as the ultimate authority with the power to raise armies and declare war. This led to a period of extreme religious persecution for non-Christians and resulted in horrific events such as the Crusades and the Inquisition. Even for Christians, the medieval period was a difficult time to be alive, as people faced war, famine, disease, and repressive social constructs.

While it is impossible to know for sure, reported miracles during this period could have been the result of two separate responses to the conditions of the time—the first being that the faithful were looking for miracles as a source of hope. Modern research shows that people—particularly those who already identify as religious—often turn to religious practices and services as a way to cope with times of trouble or sorrow. The second may be that miracles were used as a form of propaganda to justify this period of religious persecution. Academics have noted the church may have employed this strategy by communicating the lives of saints.

Reported miracles dropped as people alive during the Age of Reason espoused the concepts of empiricism, rationalism, and religious tolerance. As human understanding of the natural world evolved and science emerged to explain events that in the past would have been considered miracles, the number of declared miracles dropped sharply.

Emma Rubin // Stacker

Most Eucharistic miracles involve blood, flesh, and indestructible hosts

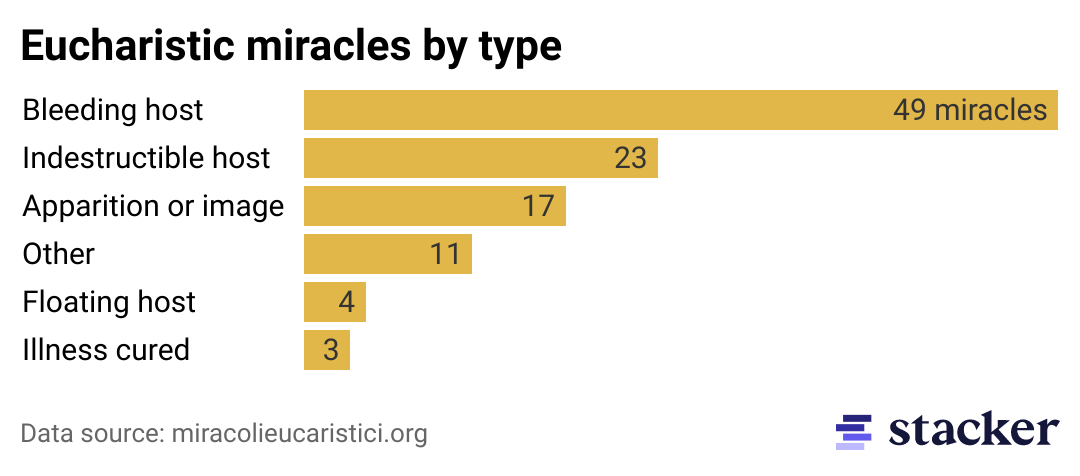

Bar chart of the most common Eucharistic miracles. Host/Wine turned to flesh and/or blood is the most common.

Every Catholic Mass includes the sacrament of Holy Communion—when the hosts and wine are consecrated through prayer and, according to the church, turned into the actual body and blood of Christ through a process called transubstantiation, which allows them to retain their physical appearance.

But in almost half of all Eucharistic miracles throughout history, the hosts, and occasionally the wine, took on the traits of real flesh and blood. The wafers have been said to drip blood or left blood stains on surfaces they came into contact with.

In the 2008 miracle of Sokolka, Poland, a bloody host taken for scientific testing by two histopathologists revealed its makeup was identical to the myocardial, or heart, tissue of a living person who was on the verge of death. The heart muscle fibers were intertwined with the bread in a way that no human could have achieved through their own intervention, according to the church’s citation of the study. There have been at least two other similar miracles where studies have allegedly revealed the presence of heart muscle fibers in the bleeding hosts. None of the research has been made publicly available.

In nearly two dozen Eucharistic miracles, hosts that should have been destroyed by floods, fire, or thieves allegedly survived unharmed. In other events, images of God appeared on the hosts.

Canva

To prove modern miracles, religion meets science

Close-up sacrament of communion.

In 2016, Pope Francis changed how the church assesses miracles, making the process more rigorous and transparent, particularly with regard to funding and scientific evaluation. An investigation three years earlier, led by a commission appointed by Pope Francis, revealed widespread failures and vulnerabilities that were being exploited. His commission found that the verification system approved by Pope St. John Paul II in 1983 led to the beatification of 1,138 persons and canonization of 482 saints—more than all his predecessors combined since 1588. It was also revealed that money played an important factor in advancing some of these individuals.

Pope Francis also declared that two-thirds of the medical board assessing miraculous events must affirm that natural causes were not at play. Previously, the confirmation process only required a majority. This medical perspective is recent in the long history of Catholicism but has been around for centuries. Pope Benedict XIV, former advocatus diaboli, served during the Age of Enlightenment and, in 1743, instituted the first order of medical experts to verify miracles in order to approve sainthood.

Data reporting by Emma Rubin. Story editing by Brian Budzynski. Copy editing by Tim Bruns.