Lompoc Cannabis Lab Averts a Shutdown Order … For Now

LOMPOC, Calif. – Central Coast Agriculture, a large cannabis manufacturing lab in Lompoc, narrowly avoided a shutdown order this week for allegedly polluting the air and failing to comply with state and federal clean air rules.

According to Aeron Arlin Genet, the Air Pollution Control Officer of Santa Barbara County, Central Coast has been manufacturing cannabis products in Lompoc — and expanding operations — since the fall of 2019, reportedly without the required permits and “best available control technology” for controlling air pollution, despite multiple warnings and notices of violations. Such “willful and knowing” violations can carry a penalty of up to $75,000 per day, she said.

In a petition to the Air Pollution Control District Hearing Board on Wednesday, Arlin Genet asked for an “abatement order” against Central Coast, claiming that the district “has been unable to secure compliance after almost three years.” The order — a rare measure that the district sees as “a severe remedy reserved for serious violators” — would have shut down the Lompoc lab immediately, throwing 122 employees out of work until proper permits could be obtained.

But at the 11th hour on Tuesday, Central Coast staved off a shutdown by submitting the final components for a complete permit application to the district. And on Wednesday, the five-member APCD Hearing Board, a quasi-judicial body, agreed to the company’s request for a 60-day extension, voting unanimously to postpone the abatement hearing to Dec. 6.

“Based on the testimony of both sides that things were moving forward with the permit application, the continuance was granted,” said Chair Terry Dressler, who formerly headed the county’s APCD. (Hearing Board members are appointed by APCD directors.)

Wednesday’s hearing was the first in the county — and perhaps in California — to consider shutting down a cannabis operation because of alleged violations of clean air rules. It’s been five years since the county’s APCD Hearing Board has considered shutting down a business of any kind . Five years ago, it was an oil and gas company that was in violation of air quality rules.

Jennifer Richardson, the district counsel, told the board, “The district’s goal in filing this petition has been to achieve compliance, not necessarily to close down a business in the county.” Central Coast, she said, had “made a lot of progress in the last couple of weeks … they’ve stopped modifying their project.”

“With the application being complete, the next steps are largely in the district’s control,” Richardson said. “We think we’ll make a lot of progress in the next 60 days.”

Noah Perch-Ahern, a lawyer for Central Coast, said the company plans to flare off emissions from the solvents it uses in manufacturing, effectively “turbo-boosting” its pollution control systems. It could take about seven months for the flare to be built and shipped from Italy, he said.

“We’re really close to the finish line,” Perch-Ahern said, adding that the company hopes to have a final permit in hand by Dec. 6. “ … This project is going to set the standard and create a model in Santa Barbara County. This is not just a sad story. There’s actually really a lot of good that’s going to come out of this.”

Round-the-clock operation

Central Coast Agriculture Inc. was co-founded by John De Friel, who is chairman of the board, and Thomas Martin, now the company’s CEO. In addition to the lab in Lompoc, Central Coast operates one of the larger outdoor cannabis grows in the county, with 54 acres under hoops at 5645 and 8701 Santa Rosa Road, west of Buellton.

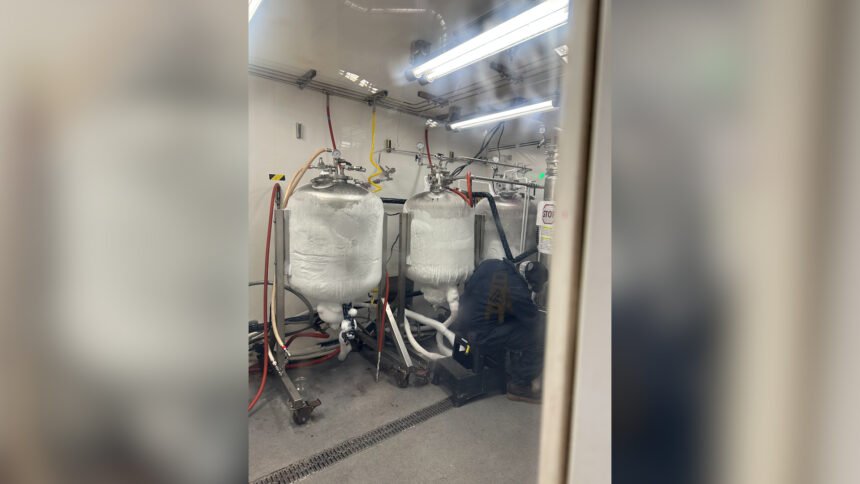

Those grows supply the raw cannabis plant material for the company’s manufacturing, extraction, storage and distribution lab, located in two warehouses at 1201 West Chestnut Ave. and 1200 West Laurel Ave. in Lompoc. It’s believed to be the largest such operation in the county and one of the largest in the state. Central Coast makes certified organic products from raw cannabis for retail sale under the “Raw Garden” trademark: vape pens, “pre-roll” joints and vaporized cannabis for medicinal purposes. The company bills its brand as “California’s best selling cannabis extracts.”

The lab in Lompoc operates 24 hours per day, seven days per week during 16 weeks of the year (the peak season); and 24 hours per day, five days per week, during the remaining 36 weeks.

In her petition, Arlin Genet, the plaintiff in the district’s case against Central Coast, alleged that the company was a major source of reactive organic compounds, the polluting gases that on hot, sunny days contribute to the production of ozone, a colorless, odorless gas that can trigger sore throats, shortness of breath and coughing.

Central Coast emitted 135 tons of reactive organic compounds in 2020 into the outside air, or twice as much as from all of the gas stations in the county, Arlin Genet said in an interview. At Central Coast, the sources of air pollution are solvents such as butane, used for extracting oils, and ethanol, used for cleaning equipment.

“This large magnitude of emissions, which correlates to operations, all occurred while in violation of district rules,” Arlin Genet said.

Specifically, her petition alleged, Central Coast officials installed their lab, added equipment, “significantly increased emissions,” changed their proposed project and failed to provide complete information about their operations, all while operating without permits, even after notices of violations were issued and the company was aware it was breaking the rules.

“No new rules”

Central Coast officials finally turned in a complete permit application to the district in August, 2022, only to report eight months later that the pollution control equipment was not working properly, the petition claimed.

Company officials said that the entire process of getting clean air permits has been complicated because there was no established “best available control technology” for cannabis extraction. The technology itself was cutting-edge, they said; Central Coast had to hire several engineering firms to design it and work out the kinks.

“It’s a case where technology outpaces regulation,” Perch-Ahern told the district Hearing Board.

But Arlin Genet called that a “mischaracterization” of how Central Coast wound up at the Hearing Board this week. The APCD’s existing clean air rules apply to the use of solvents in all manufacturing, including cannabis, she said; and in the spring of 2019, the district sent out an advisory reminding cannabis operators of those requirements.

“There are no new rules developed for cannabis,” Arlin Genet said. “Central Coast Agriculture doesn’t have permits. It’s frustrating that it took so long and that we had to take the rare step of filing for an abatement order.”

As of last month, she said, the APCD is defining “best available control technology” for cannabis manufacturing as equipment that can achieve a 95 percent reduction in air pollutants. But because Central Coast didn’t have permits, Arlin Genet said, “We haven’t been able to get to the point to fully evaluate their operations.”

Meanwhile, she said, six smaller cannabis labs in the county obtained their clean air permits from the district before they started manufacturing.

In an interview, Martin, the Central Coast CEO, said that of about 240 cannabis labs in California, his company is the only one using cold temperatures to re-condense and collect emissions and reuse solvents — a much cleaner process, he said, than burning off the excess pollution using heat from natural gas.

“We put it right back into the system and use it again,” Martin said. “Using our gases over again keeps us in line as a ‘Clean Green Certified’ operation.”

The flare that Central Coast plans to order from Italy will be small and will clean up a residual amount of emissions as a backup, using the emissions themselves as a combustion source, Martin said. All other parts of the recapture system are up and working now, he said.

“We were kind of building the plane as we flew it,” Martin said, adding that the APCD “has just been wonderful … I can’t imagine a better regulatory body to work with.”

“They see that the rest of the state is pretty dirty,” he said. “They’ve seen us take the time, spend the money and not just burn it off. We’ve been shooting for a 99 percent reduction in emissions. That’s what’s been taking us so long. We will likely have an example for the rest of the state’s operations to follow.”

In the past two years Martin said, Central Coast has not expanded but rather outsourced lab work to give the company “some breathing room to do the research and development.” The company has lost tens of millions of dollars since 2018, he said, in part because of its own dedication to the brand, but also because of low prices and a booming black market in cannabis.

“It’s a big gamble,” Martin said. “We are a money-losing organization that is passionate about the crop. We are passionate about cannabis as medicine. We’re putting up a fight to survive because of that.”

Blacked-out text

The application that Central Coast submitted to the district this week is public, but large portions have been redacted, or blacked out. Only district officials can review that information. The company considers many aspects of its operation in Lompoc to be confidential trade secrets, including the names and amounts of the solvents it uses to extract cannabis oils; and the make and model of extraction and pollution control equipment.

At Wednesday’s hearing, Steven Colome, vice-chair of the APCD Hearing Board and a retired UCLA public health researcher, said he was “somewhat surprised to see the amount of redaction” in the company’s materials, given the risk of exposure to workers and the public.

“I understand intellectual property, but sometimes the public interest and the public’s health trump intellectual property,” he said.

This week’s hearing was not the first time that Central Coast has been the target of an APCD enforcement case. Under state law, the odor from cannabis crops is exempt from district rules, but air pollution from the machinery used in cannabis manufacturing is not exempt. In mid-2021, district officials found that the company had been illegally running highly-polluting diesel generators as a primary source of power for nearly a year at his Santa Rosa Road cultivation sites. The county’s cannabis ordinance bans the use of diesel generators as a primary source of power, except in emergencies.

Diesel exhaust is a human carcinogen. The portable generators at the Santa Rosa “grows” have long since been removed, and both operations are now connected to the electrical grid. But the district and Central Coast were unable to agree on how much the company should pay in fines for breaking the law. The matter has been referred to the county District Attorney’s office, where it remains under investigation.

Melinda Burns is an investigative journalist with 40 years of experience covering immigration, water, science and the environment. As a community service, she offers her reports to multiple publications in Santa Barbara County, at the same time, for free.